03:00

Probability: Part II

Grayson White

Math 141

Week 6 | Fall 2025

Goals for Today

- Introduce Conditional Probability

- Define Independence and the Multiplication Rule

- Practice using the Law of Total Probability and Bayes’ Rule

Conditional Probability

Activity 1: Coffee or Tea?

A survey was given to 100 Math 141 students in 2017. Some results are summarized below:

| Coffee | Tea | total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-year | 7 | 10 | 17 |

| Sophomore | 25 | 20 | 45 |

| Junior | 13 | 12 | 25 |

| Senior | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| total | 53 | 47 | 100 |

What is the probability that a random student prefers coffee?

What is the probability that a random student was a sophomore?

What is the probability that a random student was a sophomore and preferred coffee?

What is the probability that a random sophomore preferred coffee?

Conditional Probability

Conditional Probability: probability of something occurring, given that another event has already occurred.

We write the conditional probability of Event A given Event B has occurred as,

\[P(A\ | \ B)\]

In the previous example,

- Question: What is the probability that a random sophomore preferred coffee?

- Event A: The student prefers coffee

- Event B: The student is a sophomore

- Answer: P(Coffee | Sophomore) = P(A|B)

Conditional Probability

How do we calculate conditional probabilities?

\[ P(\text{Coffee} | \text{Sophomore} ) = \frac{P(\text{Sophomore and prefers Coffee})}{P(\text{Sophomore})} \]

In general,

Theorem: Conditional Probability Rule

The Conditional Probability of an event \(A\) given another event \(B\) is \[ P(A | B)= \frac{P(A \textrm{ and } B)}{P(B)} \]

Answers to Activity 1

- Event \(A\): The student prefers coffee

- Event \(B\): The student is a sophomore

- Probability student prefers coffee: \(P(\text{Coffee}) = P(A) = \frac{53}{100}\)

- Probability student is a sophomore: \(P(\text{Sophomore}) = P(B) = \frac{45}{100}\)

- Probability student is a sophomore and prefers coffee: \(P(\text{Sophomore and Coffee}) = P(\text{A and B}) = \frac{25}{100}\)

- Probability a random sophomore prefers coffee: \[P(\text{A | B}) = \frac{P(\text{A and B})}{P(\text{B})} = \frac{25}{100}\Big/\frac{45}{100} = \frac{25}{45}\]

Using Conditional Probability

Using Conditional Probabilities…

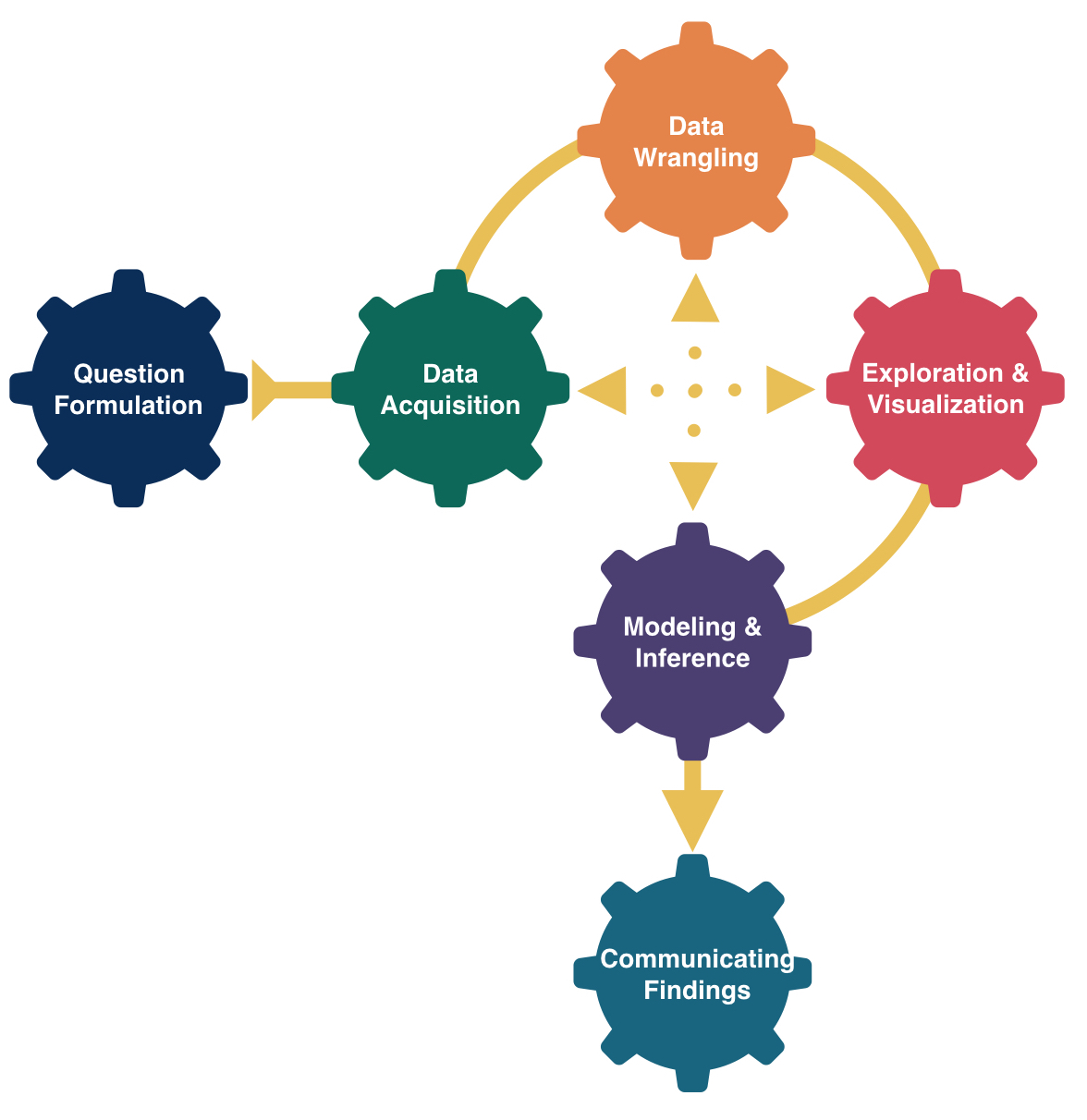

In the next few slides, we’re going to use the concept of conditional probability to explore 4 more concepts:

Independence

Multiplication Rule

Law of Total Probability

Bayes’ Rule

Independence

We say two events are independent if knowing one occurs doesn’t change the probability that another occurs.

- For example, rolling a 3 on a die (event A) doesn’t change the probability that it rains today (event B), so these two events are independent.

Theorem: Criteria for Independence

Two events \(A\) and \(B\) are independent if and only if \[ P(A | B) = P(A) \quad \text{and} \quad P(B | A) = P(B) \]

Q: Are the events “preferring coffee” (A) and “being a sophomore at Reed” (B) independent?

No! That’s because \(P(A)=\frac{53}{100}\) and \(P(A|B)=\frac{25}{45}\), so \(P(A)\neq P(A|B)\)

Multiplication Rule

What if we want to know the probability that two events both occur?

Rearrange our formula for conditional probability!

\[\begin{align} P(A | B)&= \frac{P(A \textrm{ and } B)}{P(B)} \\ \implies P(A | B) P(B) &= P(A \textrm{ and } B) \end{align}\]

Theorem: Multiplication Rule

For any events \(A\) and \(B\), \[ P(A \textrm{ and } B ) = P(A|B) \times P(B) \]

Multiplication Rule

Theorem: Multiplication Rule

For any events \(A\) and \(B\), \[ P(A \textrm{ and } B ) = P(A|B) \times P(B) \]

In the previous example…

- Event \(A\): The student prefers coffee

- Event \(B\): The student is a sophomore

and

- \(P(B) = \frac{45}{100}\)

- \(P(A|B) = \frac{25}{45}\)

- \(P(A \ \text{and} \ B) = \frac{25}{100}\)

Does it work?

\[ P(A|B) P(B) = (\frac{25}{45}) (\frac{45}{100}) = \frac{25}{100}\]

Checks out!

The Law of Total Probability

Consider two events:

- Event \(A\): The student prefers coffee

- Event \(B\): The student is a sophomore

In this scenario, notice for any student who prefers coffee (\(A\)), it’s possible…

- they’re a sophomore (\(B\))

- they’re not a sophomore (\(B^c\))

Thus, \[ \begin{align} P(A) &= P(A\text{ and }B) + P(A\text{ and }B^c) \tag{Addition Rule}\\ &=P(A | B)P(B) + P(A|B^c)P(B^c) \tag{Multiplication Rule} \end{align} \]

The Law of Total Probability

Theorem: The Law of Total Probability

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be events. Then \[ P(A) = P(A | B)P(B) + P(A | B^c)P(B^c) \]

- The Law of Total Probability is useful when finding “overall” probabilities when we only have the “pieces”.

- We’ll see a real-world example next!

Patient Health

Suppose you’re a medical researcher interested in population health.

- 80% of individuals see a physician each year

- 20% do not

- Among people who see a physician, 95% are generally healthy.

- Among people who don’t see a physician, 70% are generally healthy.

Q: What proportion of adults are generally healthy?

Let

- Event \(A\): Individual is healthy

- Event \(B\): Individual sees a physician each year

- Event: \(B^c\): Individual doesn’t see a physician each year

This question is asking: \(P(A)=\)???

Patient Health

Theorem: The Law of Total Probability

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be events. Then \[ P(A) = P(A | B)P(B) + P(A | B^c)P(B^c) \]

We want to answer \(P(\text{Healthy})\).

Note that,

\[ \begin{align} P(\text{Healthy}) &= P(\text{Healthy}|\text{Doctor})P(\text{Doctor})+P(\text{Healthy}|\text{Doctor}^c)P(\text{Doctor}^c)\\ &= P(A|B)P(B) + P(A|B^c)P(B^c)\\ &= (.95)(.80) + (.70)(.20)\\ &= 0.90 \end{align} \]

Thus, 90% of adults are generally healthy!

Bayes’ Rule

What if we know \(P(B|A)\), but we want to know \(P(A|B)\)?

Theorem: Bayes’ Rule

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be events. Then, \[ P(A|B) = \frac{P(B | A)P(A)}{P(B)} \]

Proof: From the definition of multiplication rule, \[ \begin{align} P(A \text{ and } B) &= P(A|B)\times P(B)\\ P(A \text{ and } B) &= P(B|A)\times P(A) \end{align} \]

Setting these two equations equal, we find \[ \begin{align} P(A|B)\times P(B) &= P(B|A)\times P(A)\\ \implies P(A|B) &= \frac{P(B|A)P(A)}{P(B)} \end{align} \]

Activity

Activity 2: Testing for a Rare Disease

Suppose that we have a rapid COVID-19 test that:

- Given a person does not have COVID, the test is (correctly) negative 99% of the time.

- Given a person does have COVID, the test is (correctly) positive 80% of the time.

Assume that the overall prevalence of COVID at the time of the test was 1%.

Q: Suppose a person takes this test and receives a positive diagnosis – what is the probability that the person has COVID?

- Hint 1: Write this out in terms of a conditional probability

- Hint 2: Define events \(A\) or \(B\) in this setting (as well as \(A^c\) and \(B^c\))

- Hint 3: Write out all the info here in terms of probabilities and events \(A\) and \(B\).

- Hint 4: Start with Bayes’ Rule! You’ll also need the Law of Total Probability!

12:00

Activity 2: Solution

Q: Suppose a person takes this test and receives a positive diagnosis – what is the probability that the person has COVID?

- This is asking for \(P(\text{Have Covid} \ | \ \text{Positive Test})\)

- \(A\) = Has COVID, \(A^c\) = No COVID, \(B\) = Positive Test, \(B^c\) = Negative Test

- Express what we know using probability language…

Activity 2: Solution

Test correctly diagnoses a person who does not have COVID 99% of the time

\(P(B^c | A^c) = 0.99\) and \(P(B | A^c) = 0.01\)Test correctly diagnoses a patient who does have COVID 80% of the time.

\(P(B | A) = 0.80\) and \(P(B^c | A) = 0.20\)The overall prevalence of COVID at the time of the test was 1%.

\(P(A) = 0.01\) and \(P(A^c) = 0.99\)

Bayes’ Rule:

\[ P (A | B) = P(B | A) \frac{P(A)}{P(B)} = 0.80 * \frac{0.01}{P(B)=\text{???}} \]

Law of Total Probability:

\[ P (B) = P(B | A) P(A) + P(B | A^c) P(A^c) = 0.80(0.01) + 0.01(0.99) = 0.0179 \]

Combining the above:

\[ \implies P (A | B) = 0.80 * \frac{0.01}{0.0179} \approx \boxed{0.447} \]

Bonus Activity: Bayes’ Rule

Theorem: Bayes’ Rule

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be events. Then \[ P(A|B) = \frac{P(B | A)P(A)}{P(B)} \]

Q: Consider Bayes’ Rule. Under what circumstances will \(P(A|B) = P(B|A)\)?

Q: Suppose \(P(B|A) = 1\):

- What does this suggest about \(A\) and \(B\)?

- What is \(P(A|B)\) in this case?

Bonus Activity: Answers

Theorem: Bayes’ Rule

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be events. Then \[ P(A|B) = \frac{P(B | A)P(A)}{P(B)} \]

Q: Under what circumstances will \(P(A|B) = P(B|A)\)?

Answer: Whenever \(P(A)=P(B)\)

Q: Suppose \(P(B|A) = 1\):

- What does this suggest about \(A\) and \(B\)?

A: Whenever A occurs, so does B.

- What is \(P(A|B)\) in this case?

A: \(P(A|B) = P(A)/P(B)\)