Computing Power

Grayson White

Math 141

Week 9 | Fall 2025

Goals for Today

- Review decisions in a hypothesis test

- Types of errors

- Learn to compute the power of a hypothesis test

Recall: Hypothesis Testing Framework

Set-up hypotheses:

- Be able to express in words and in terms of parameters.

Collect data.

Assume \(H_o\) is correct.

Compute a p-value to quantify the likelihood of the sample results using a test statistic.

Draw a conclusion about the alternative hypothesis.

Recall: Types of errors

- \(\alpha\) = prob of Type I error under repeated sampling = prob reject \(H_o\) when it is true

- \(\beta\) = prob of Type II error under repeated sampling = prob fail to reject \(H_o\) when \(H_a\) is true.

Question: How are \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) related? What happens to \(\beta\) if we decrease \(\alpha\)?

Hypothesis Testing: Decisions, Decisions

Question: How do I select \(\alpha\)?

Will depend on the convention in your field.

Want a small \(\alpha\) and a small \(\beta\). But they are related.

- The smaller \(\alpha\) is the larger \(\beta\) will be.

Choose a lower \(\alpha\) (e.g., 0.01, 0.001) when the Type I error is worse and a higher \(\alpha\) (e.g., 0.1) when the Type II error is worse.

Can’t easily compute \(\beta\). Why?

One more important term:

- Power = probability reject \(H_o\) when the alternative is true.

Example

Suppose we have a baseball player who has been a 0.250 career hitter who suddenly improves to be a 0.333 hitter. He wants a raise but needs to convince his manager that he has genuinely improved. The manager offers to examine his performance in 20 at-bats.

Ho:

Ha:

When \(\alpha\) is set to \(0.05\), he needs to hit 9 or more to get a small enough p-value to reject \(H_o\).

When \(\alpha\) is set to \(0.05\), the power of this test is 0.182.

Why is the power so low?

What aspects of the test could the baseball player change to increase the power of the test?

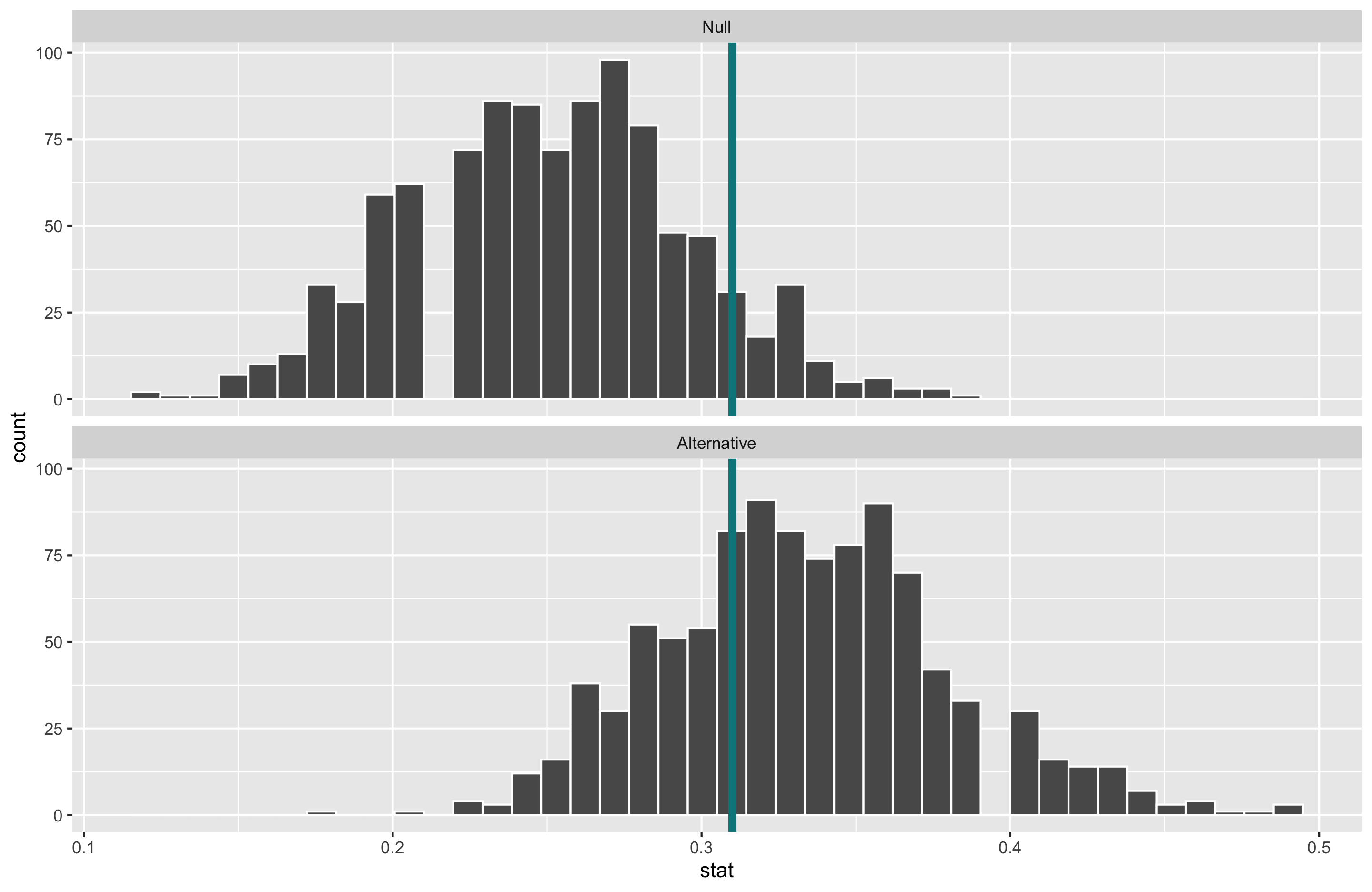

Example

Suppose we have a baseball player who has been a 0.250 career hitter who suddenly improves to be a 0.333 hitter. He wants a raise but needs to convince his manager that he has genuinely improved. The manager offers to examine his performance in 20 100 at-bats.

What will happen to the power of the test if we increase the sample size?

Increasing the sample size increases the power.

When \(\alpha\) is set to \(0.05\) and the sample size is now 100, the power of this test is 0.57.

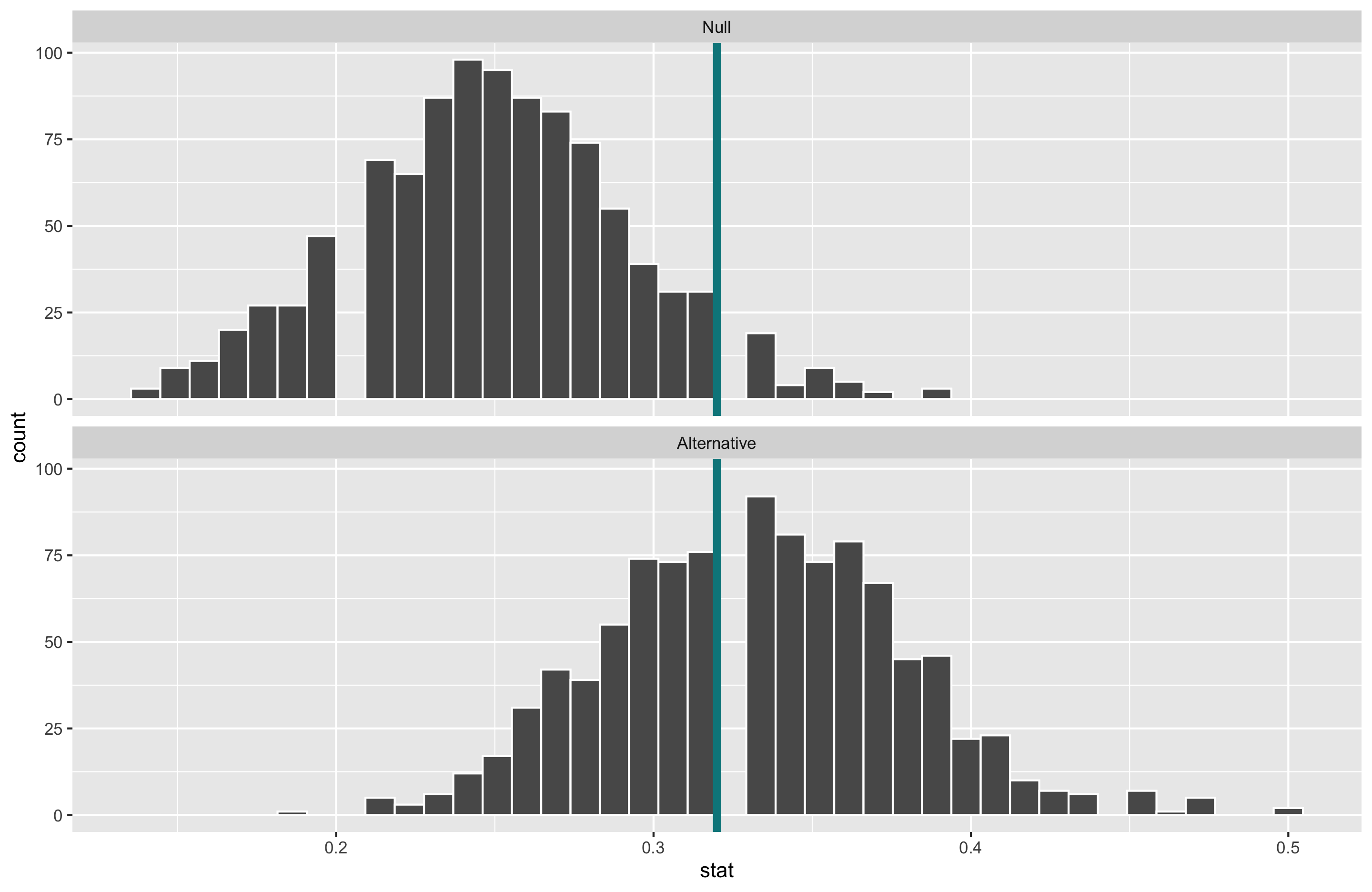

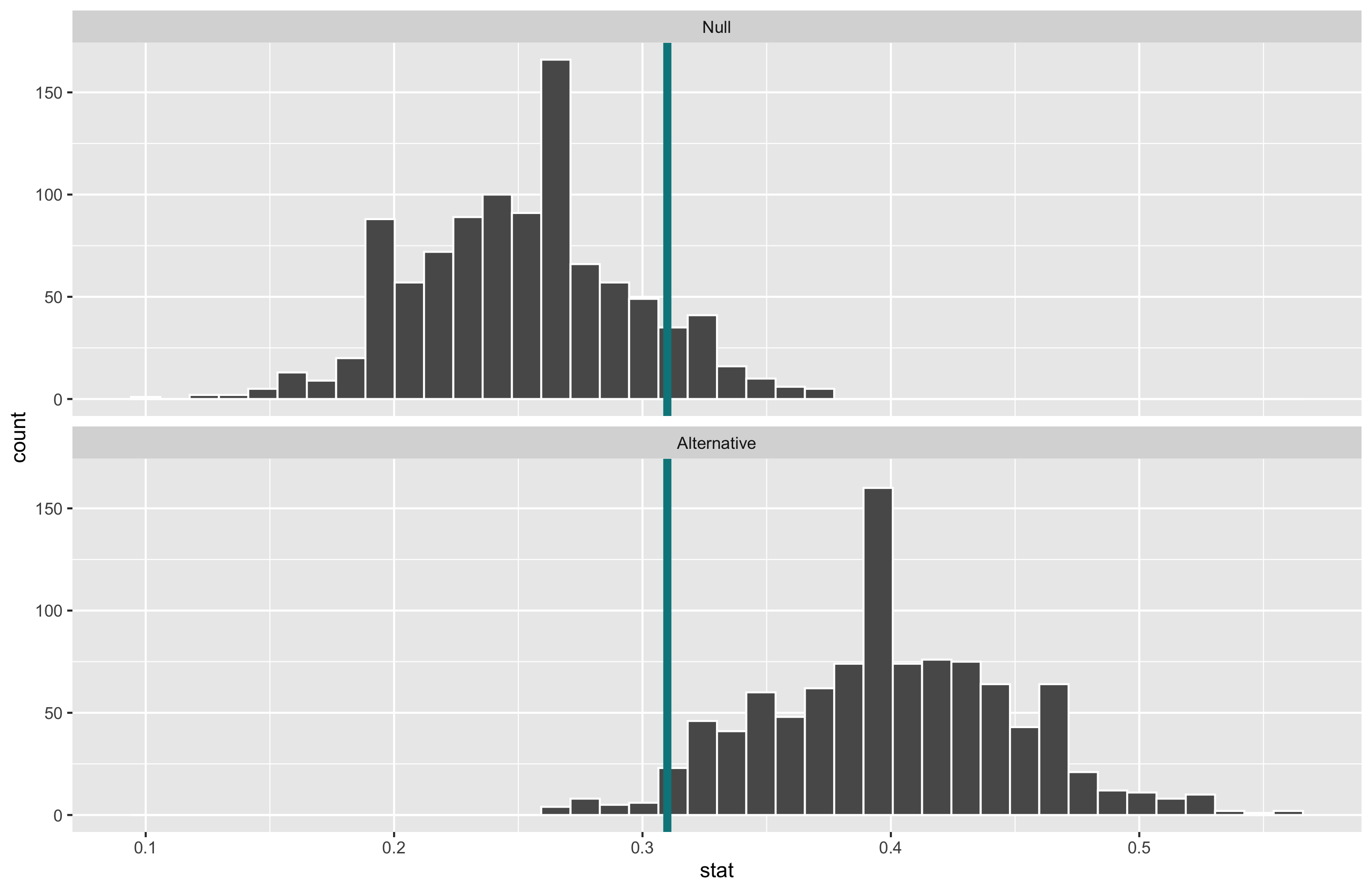

Example

Suppose we have a baseball player who has been a 0.250 career hitter who suddenly improves to be a 0.333 hitter. He wants a raise but needs to convince his manager that he has genuinely improved. The manager offers to examine his performance in 20 100 at-bats.

What will happen to the power of the test if we increase \(\alpha\) to 0.1?

- Increasing \(\alpha\) increases the power.

- Decreases \(\beta\).

- When \(\alpha\) is set to \(0.1\) and the sample size is 100, the power of this test is 0.65.

Example

Suppose we have a baseball player who has been a 0.250 career hitter who suddenly improves to be a 0.333 0.400 hitter. He wants a raise but needs to convince his manager that he has genuinely improved. The manager offers to examine his performance in 20 100 at-bats.

What will happen to the power of the test if he is an even better player?

Effect size: Difference between true value of the parameter and null value.

- Often standardized.

Increasing the effect size increases the power.

When \(\alpha\) is set to \(0.1\), the sample size is 100, and the true probability of hitting the ball is 0.4, the power of this test is 0.95.

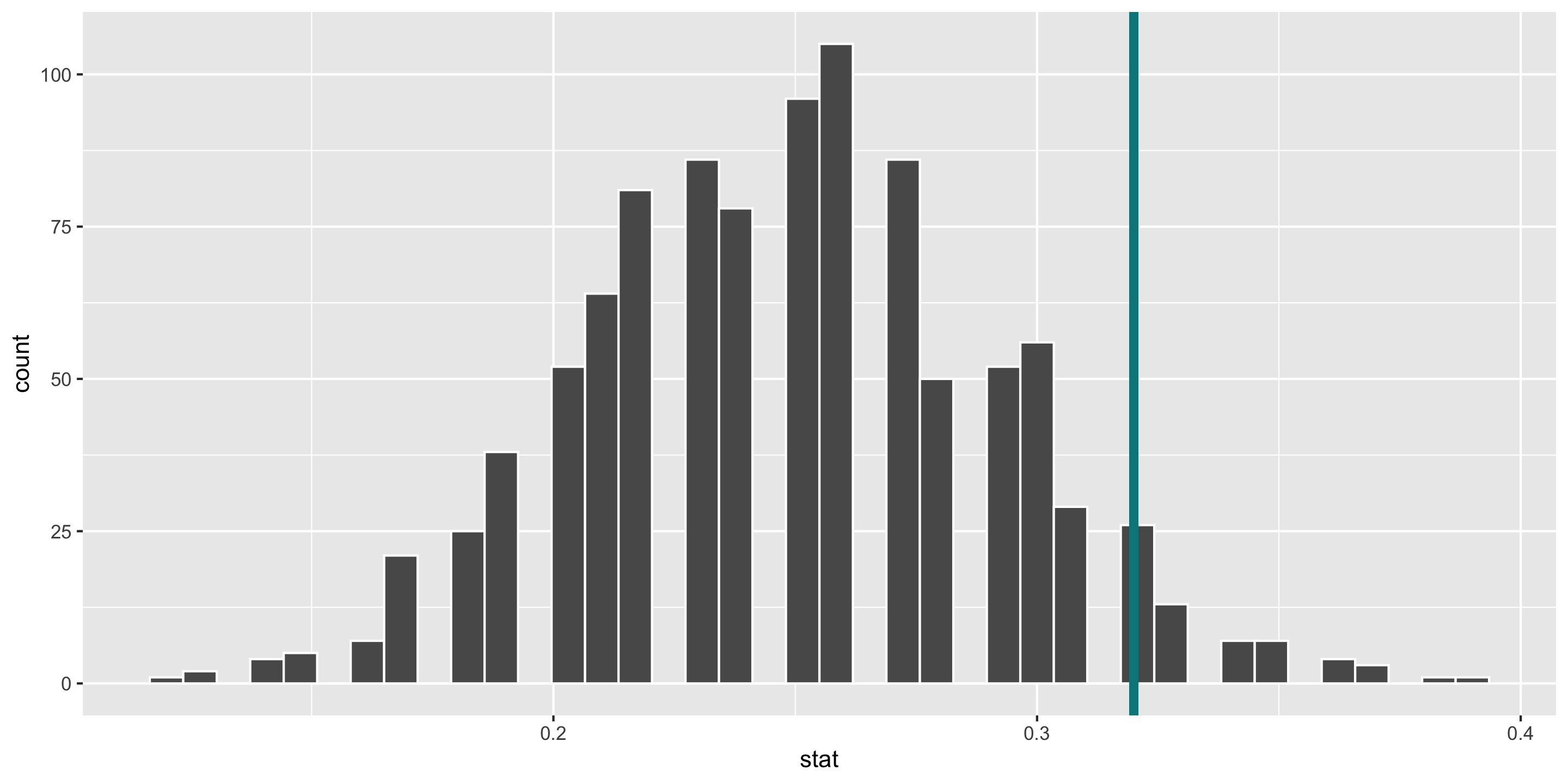

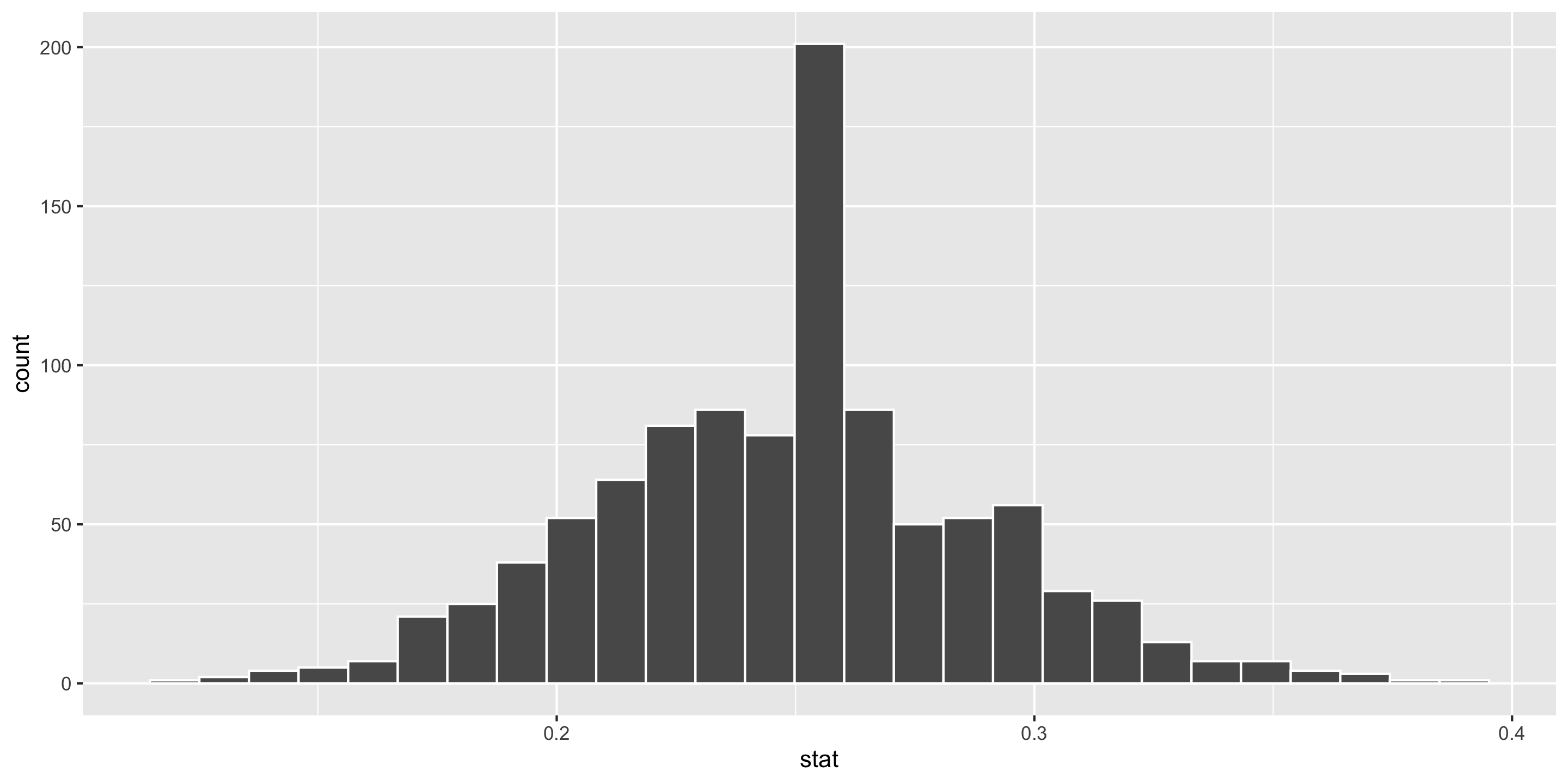

Computing Power

- Generate a null distribution:

# Create a dummy dataset with the correct sample size

dat <- data.frame(at_bats = c(rep("hit", 80),

rep("miss", 20)))

null <- dat %>%

specify(response = at_bats, success = "hit") %>%

hypothesize(null = "point", p = 0.25) %>%

generate(reps = 1000, type = "draw") %>%

calculate(stat = "prop")

ggplot(data = null, mapping = aes(x = stat)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 27, color = "white")

Computing Power

- Determine the “critical value(s)” where \(\alpha = 0.05\)

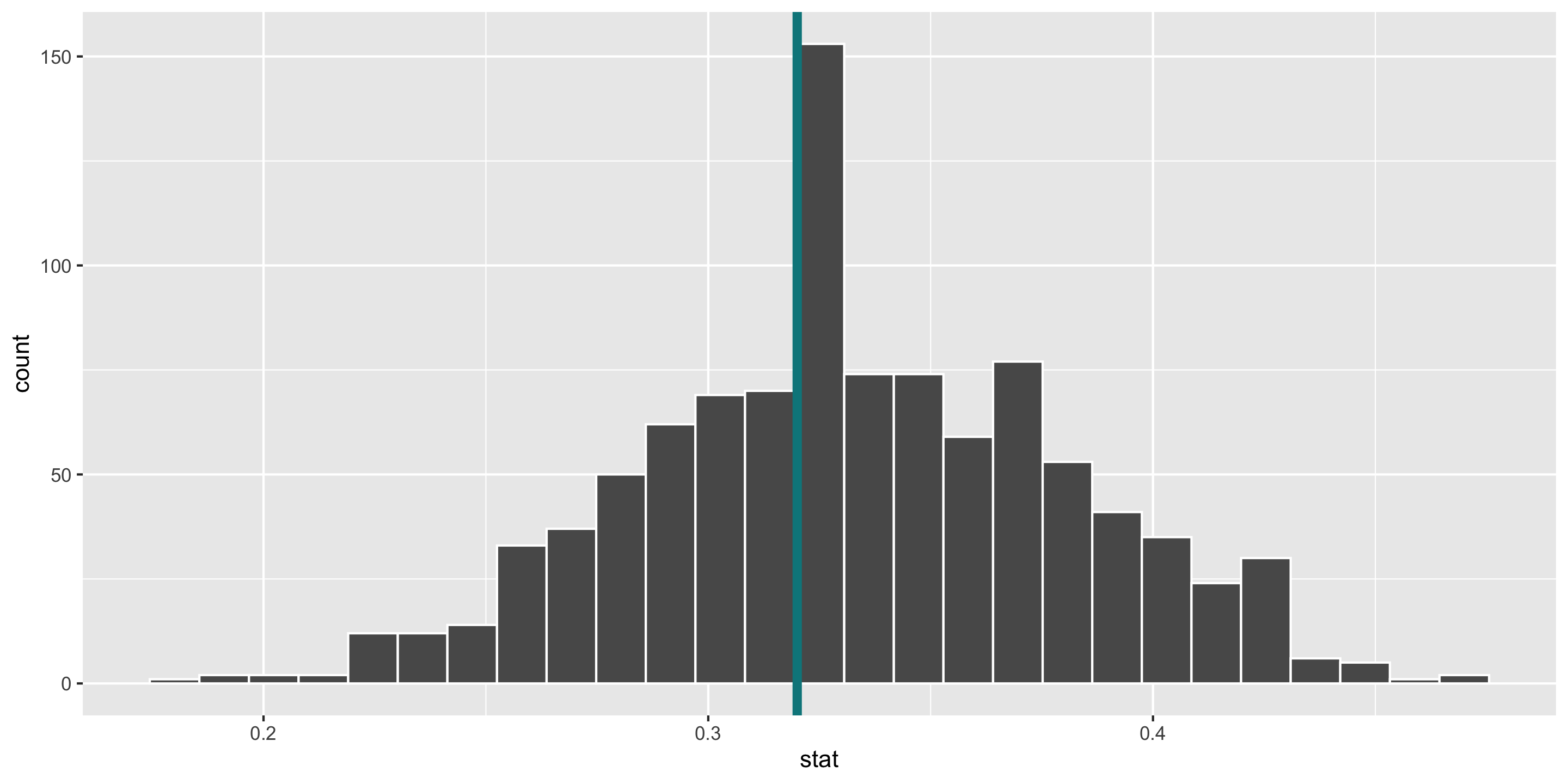

Computing Power

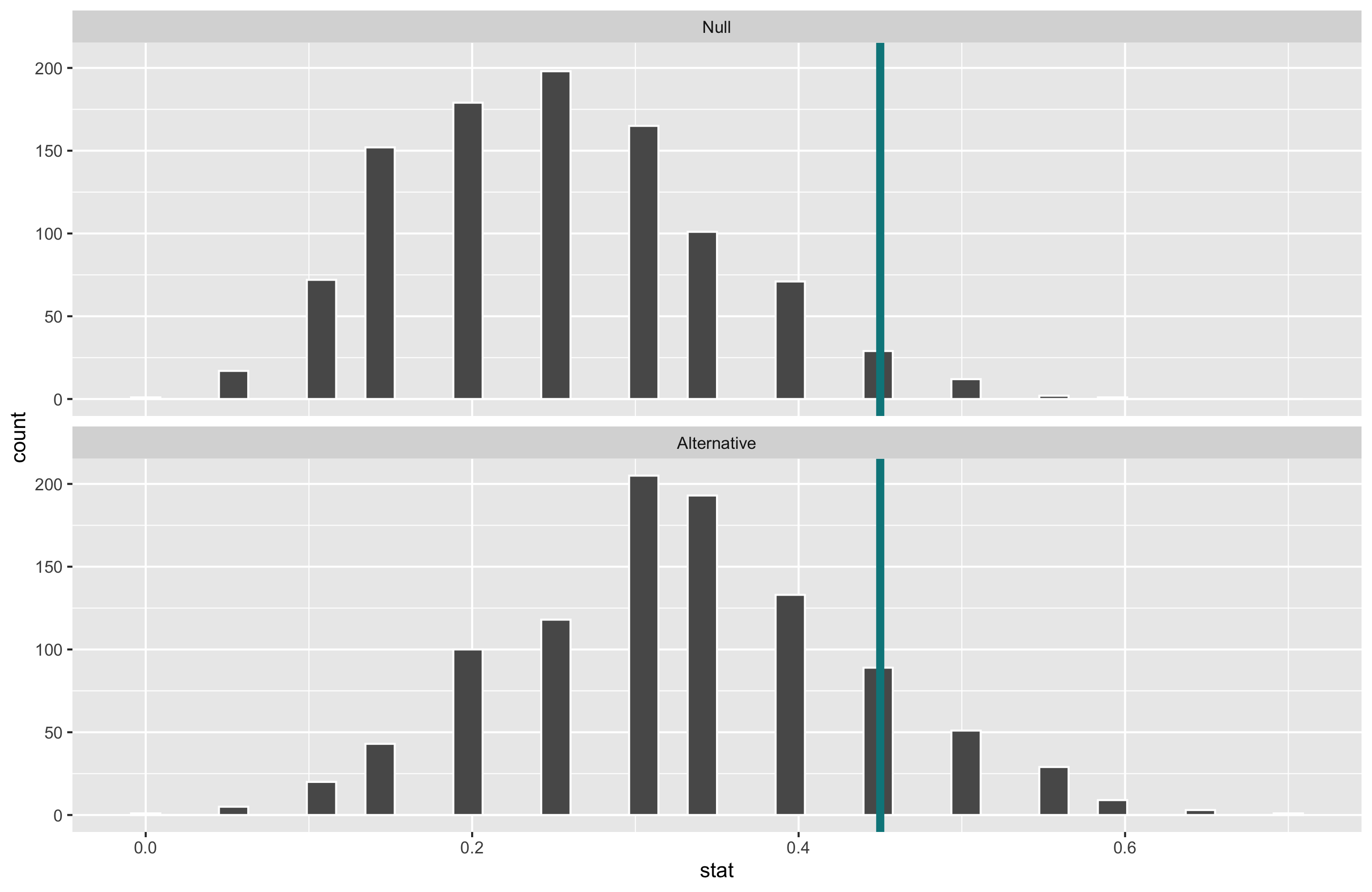

- Construct the alternative distribution.

alt <- dat %>%

specify(response = at_bats, success = "hit") %>%

hypothesize(null = "point", p = 0.333) %>%

generate(reps = 1000, type = "draw") %>%

calculate(stat = "prop")

ggplot(data = alt, mapping = aes(x = stat)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 27, color = "white") +

geom_vline(xintercept = quantile(null$stat, 0.95),

size = 2,

color = "turquoise4")

Computing Power

- Find the probability of the critical value or more extreme under the alternative distribution.

Thoughts on Power

What aspects of the test did the player actually have control over?

Why is it easier to set \(\alpha\) than to set \(\beta\) or power?

Considering power before collecting data is very important!

The danger of under-powered studies

- EX: Turning right at a red light

Reporting Results in Journal Articles

Next time:

- \(p\)-value pitfalls

- Introduce random variables!