Random Variables III

Grayson White

Math 141

Week 10 | Fall 2025

Goals for Today

- Discuss continuous random variables

- Introduce the normal distribution

- Introduce the \(t\) distribution

- Discuss the Central Limit Theorem!

Continuous Random Variables

The Distribution of a Continuous Variable

If \(X\) is a continuous random variable, it can take on any value in an interval.

- e.g., \(0\leq X\leq 10\) or \(-\infty < X < \infty\)

Recall: For discrete random variables, we could list the probability of each possible outcome.

- For continuous random variables, this won’t work. There are infinite outcomes!

Instead, we represent relative chances of different possible outcomes using a density function \(f(X)\)

- \(f(X) \geq 0\) for all possible \(X\)

- The total area under the function is \(1\)

- \(P(a\leq X\leq b)\) is the area under \(f\) between \(a\) and \(b\)

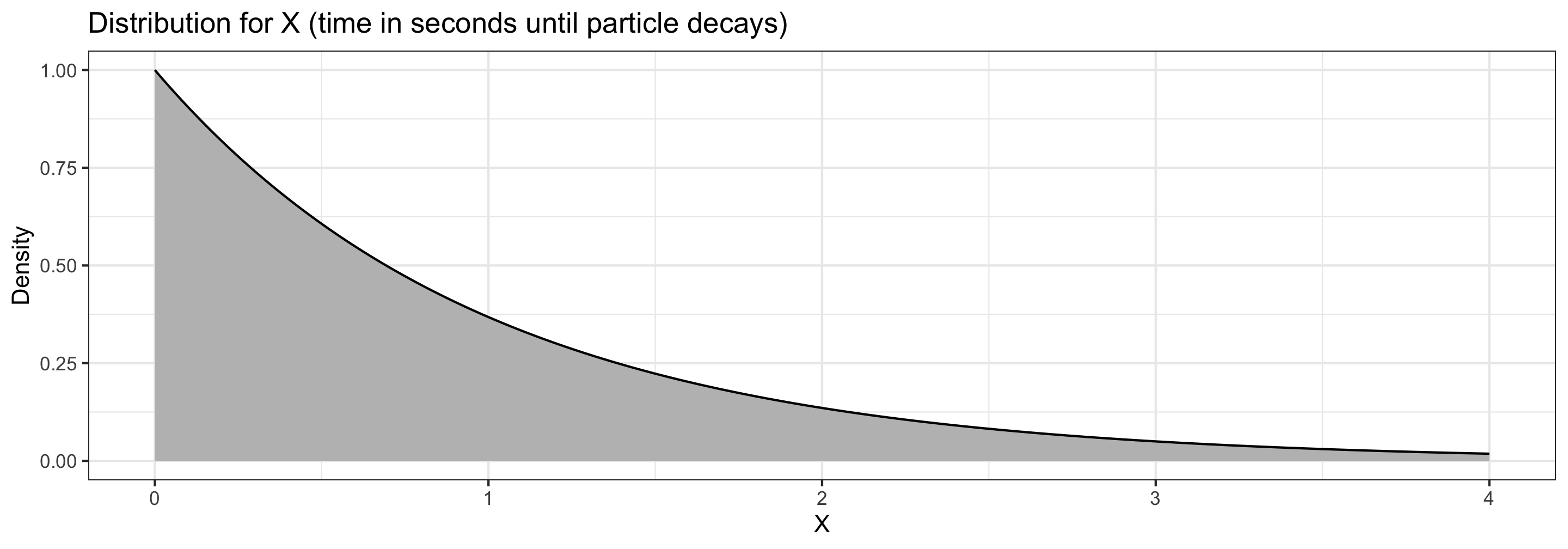

Density Curve

Suppose \(X\) is a random variable representing the time (in seconds) it takes for a particle to experience radioactive decay, where \[ f(x) = e^{-x} \qquad \textrm{for } x\geq 0 \]

- The probability that it takes between \(1\) and \(2\) seconds to decay is the area under the curve between \(1\) and \(2\). \(P(1 < T < 2) =\)

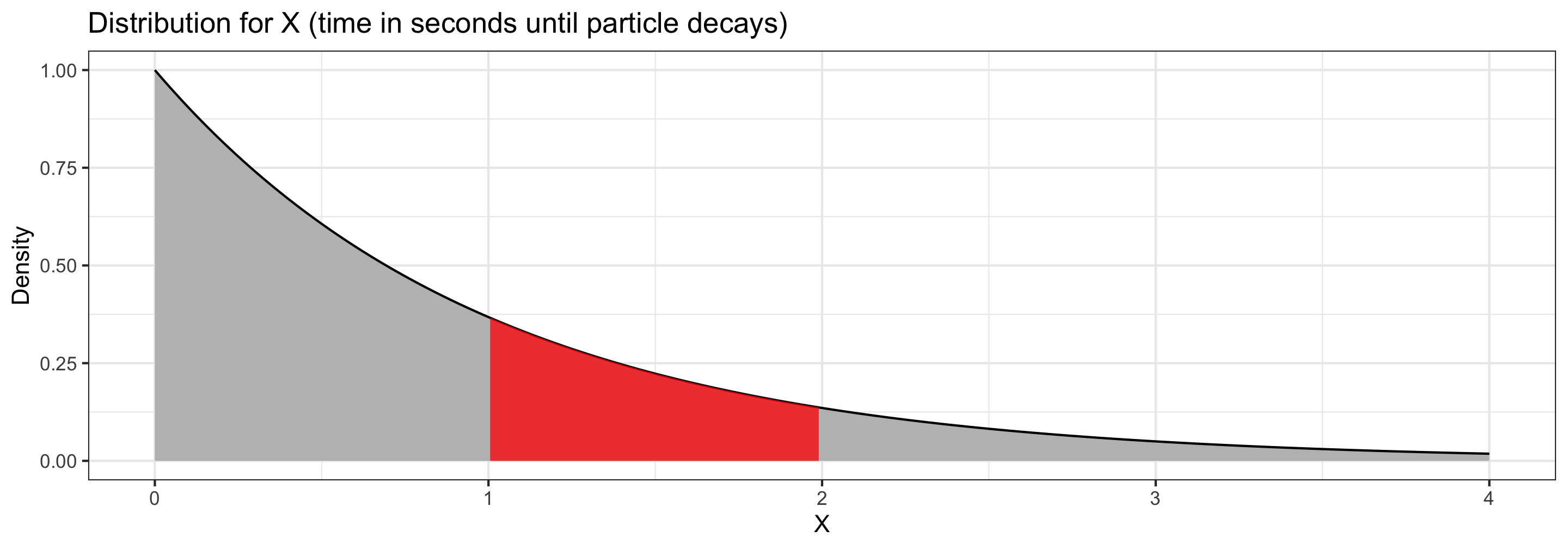

Density Curve

Suppose \(X\) is a random variable representing the time (in seconds) it takes for a particle to experience radioactive decay, where \[ f(x) = e^{-x} \qquad \textrm{for } x\geq 0 \]

- The probability that it takes between \(1\) and \(2\) seconds to decay is the area under the curve between \(1\) and \(2\). \(P(1 < T < 2) = \color{red}{0.232}\)

Mean and Variance

Continuous variables have a mean, variance, and standard deviation too!

- We can’t use the same definition as for discrete random variables. \[E[X] = \sum_x xP[X=x]\]

- There are infinitely many values

- With infinitely many, each specific one has probability 0

Instead, we have to use calculus to define mean and variance: \[ \begin{align} E[X] &= \int x f(x) \, dx\\ \mathrm{Var}(X) &= \int (x - \mu)^2 f(x) \, dx \end{align} \]

Mean and Variance

\[ \begin{align} E[X] &= \int x f(x) \, dx\\ \mathrm{Var}(X) &= \int (x - \mu)^2 f(x) \, dx\\ \mathrm{SD}(X) &=\sqrt{\mathrm{Var}(X)} \end{align} \]

- These integrals are tools to meaningfully average infinitely many values

- (We won’t compute any integrals in this class!)

As always…

- the mean of a random variable represents a typical value.

- the standard deviation represents the typical size of deviations from the mean.

The Normal Distribution

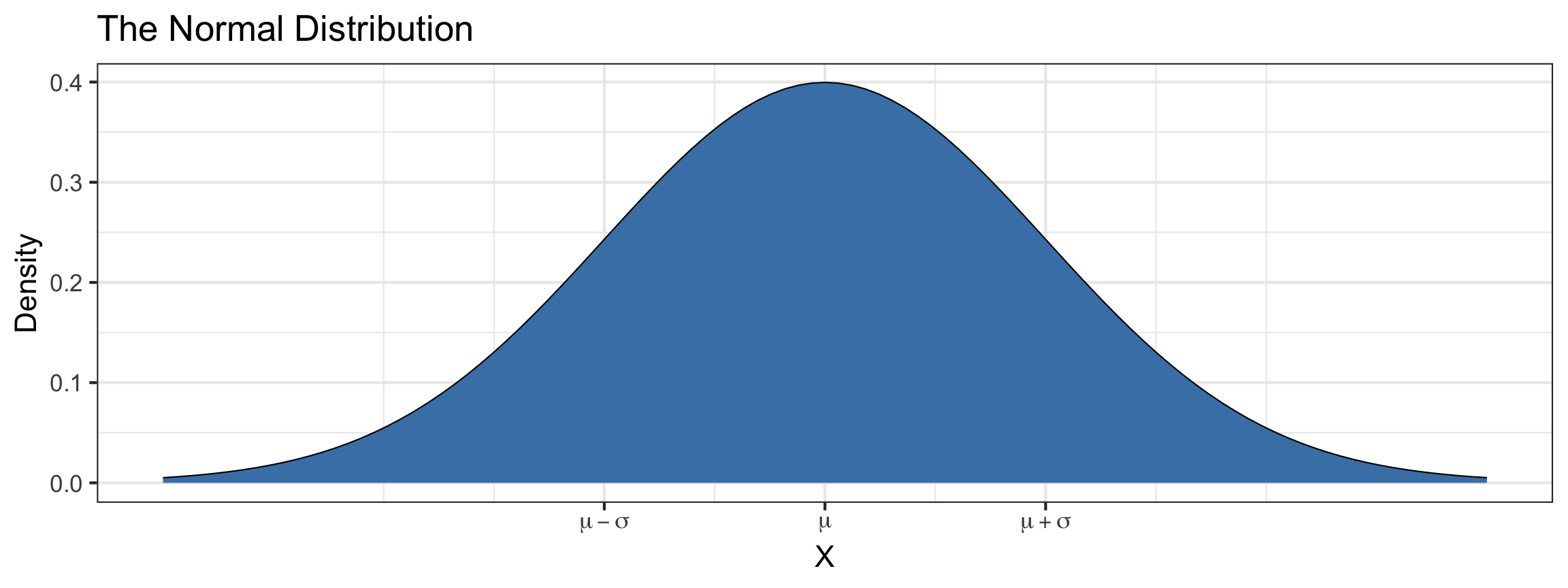

The Normal Distribution

The Normal distribution is defined by two parameters:

- Mean, \(\mu\)

- Standard deviation, \(\sigma\)

Suppose \(X\) follows a Normal(\(\mu\),\(\sigma\)) distribution. The density function is \[f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}} \cdot\exp \left(\frac{-(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right)\]

Calculating Probabilities

R has built-in functions for calculating probabilities from a normal distribution.

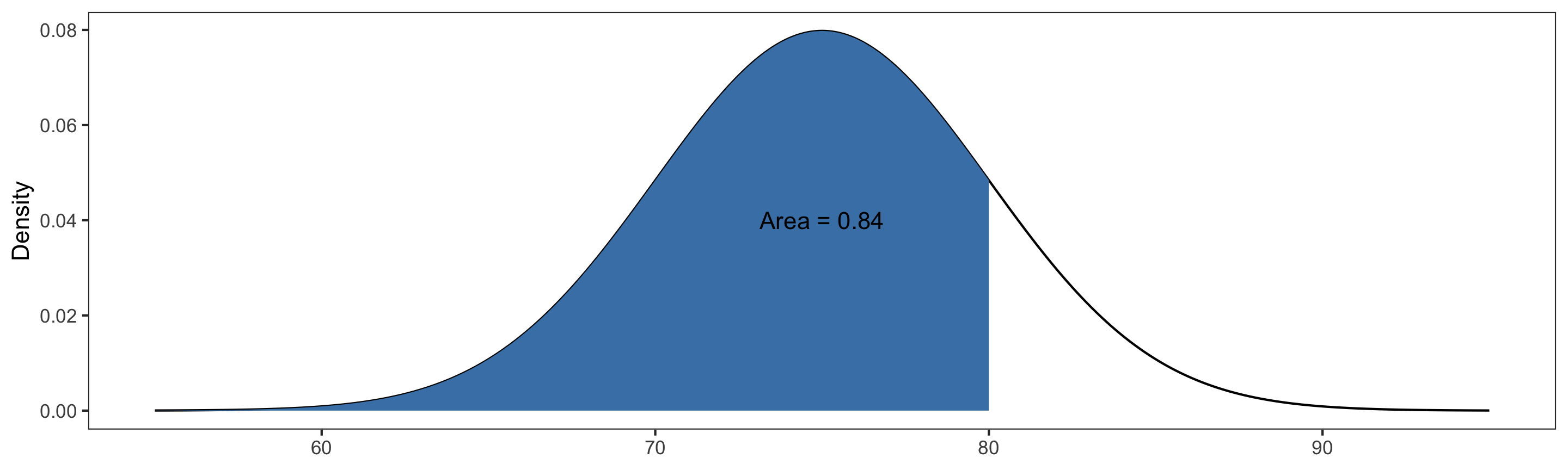

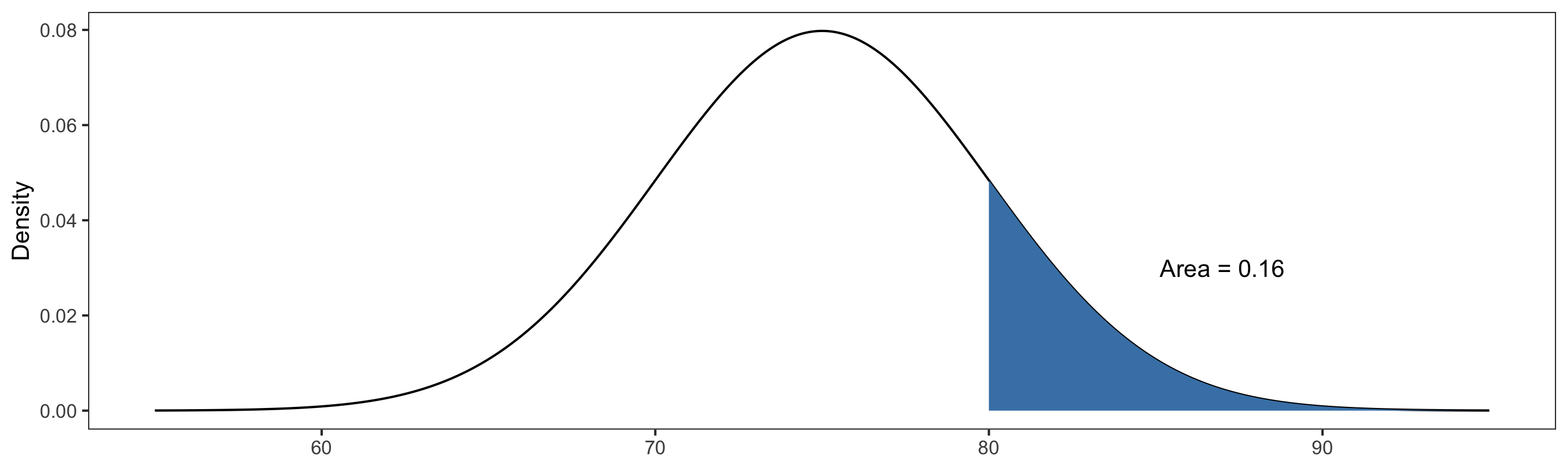

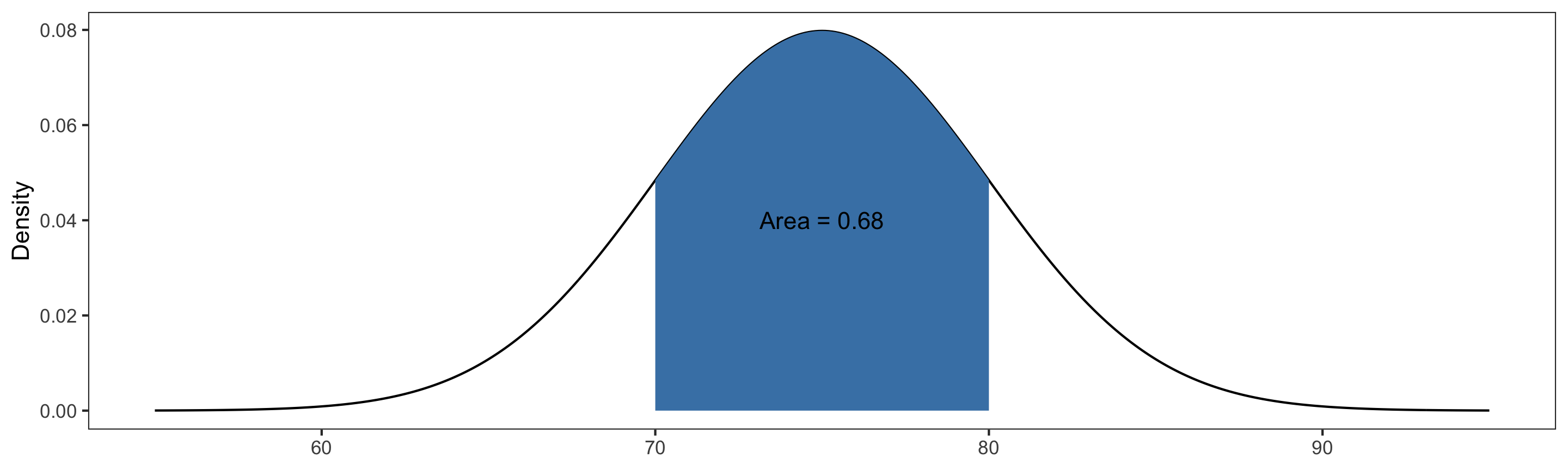

Suppose \(X\sim \text{Normal}(\mu=75, \sigma=5)\). Then:

Calculating Probabilities

R has built-in functions for calculating probabilities from a normal distribution.

Suppose \(X\sim \text{Normal}(\mu=75, \sigma=5)\). Then:

Calculating Probabilities

R has built-in functions for calculating probabilities from a normal distribution.

Suppose \(X\sim \text{Normal}(\mu=75, \sigma=5)\). Then:

- \(P(70 \leq X \leq 80) = P(X\leq 80) - P(X\leq 70) =\)

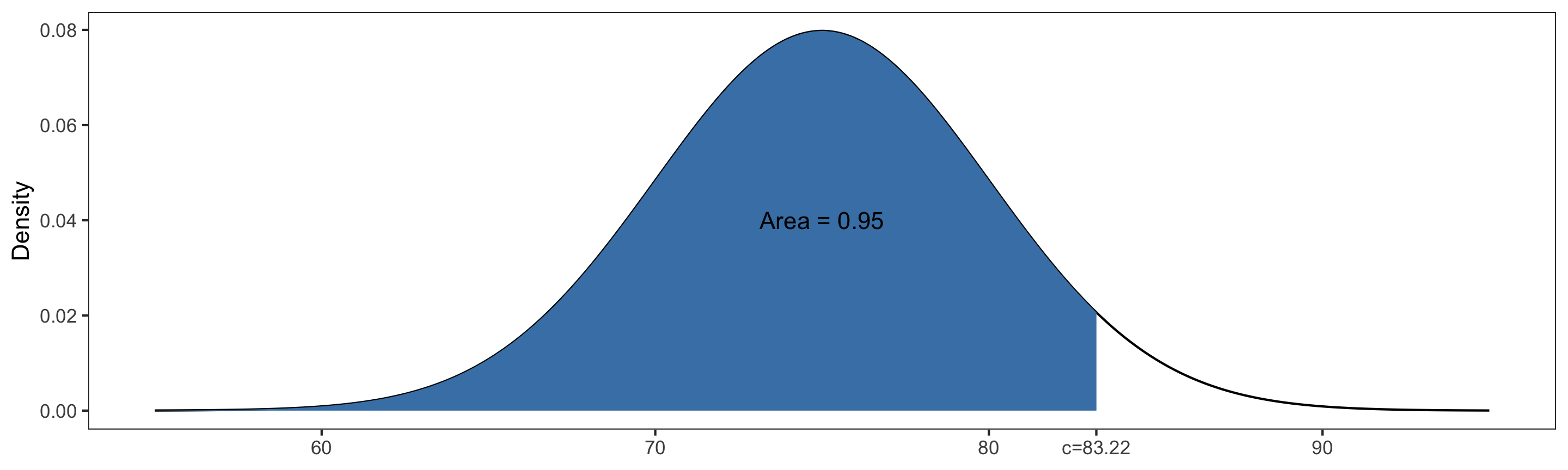

Finding Quantiles

We can also use R to find quantiles of a Normal distribution.

Suppose \(X\sim \text{Normal}(\mu=75, \sigma=5)\). Then:

Scale and Translation Invariance

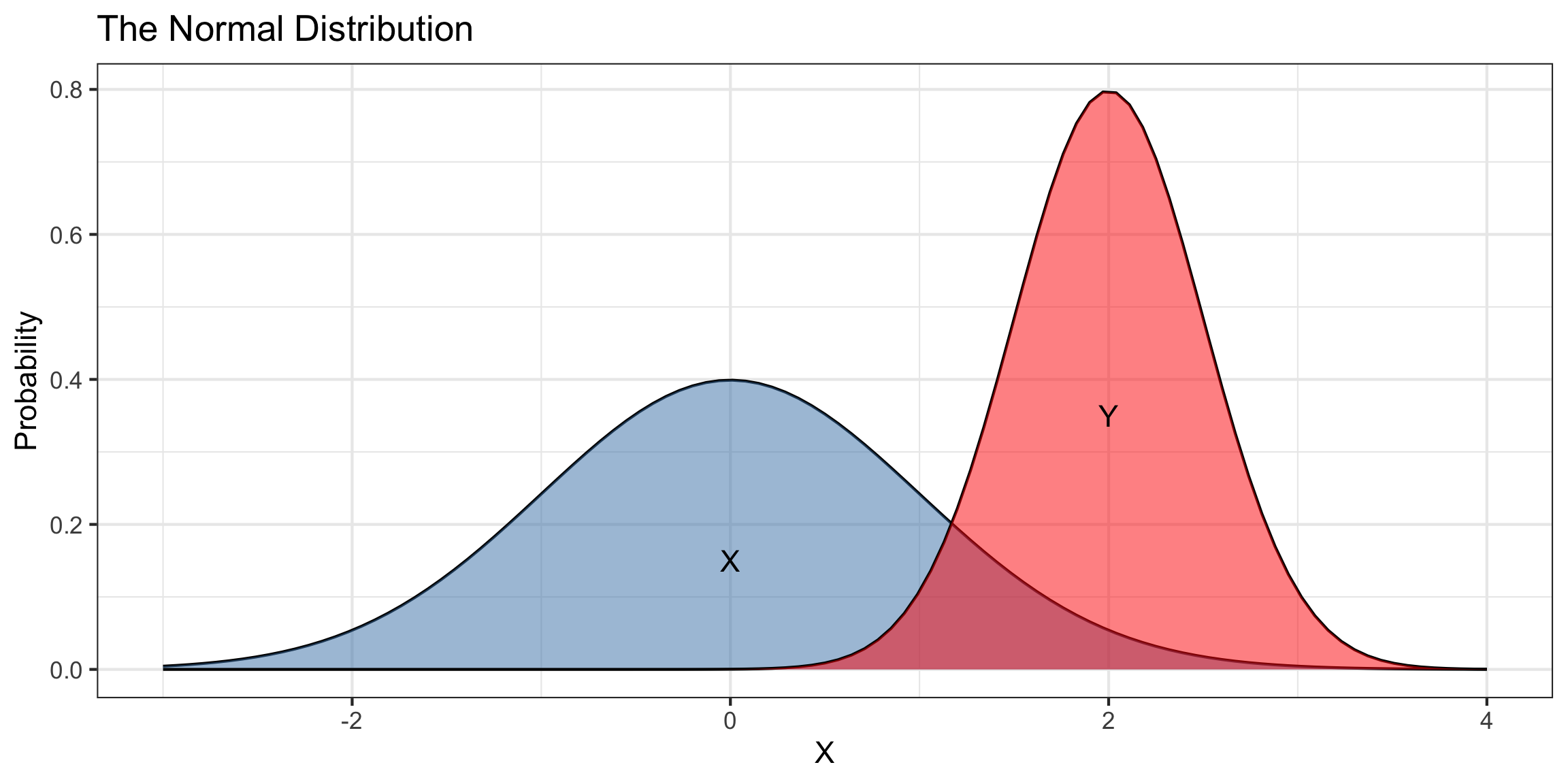

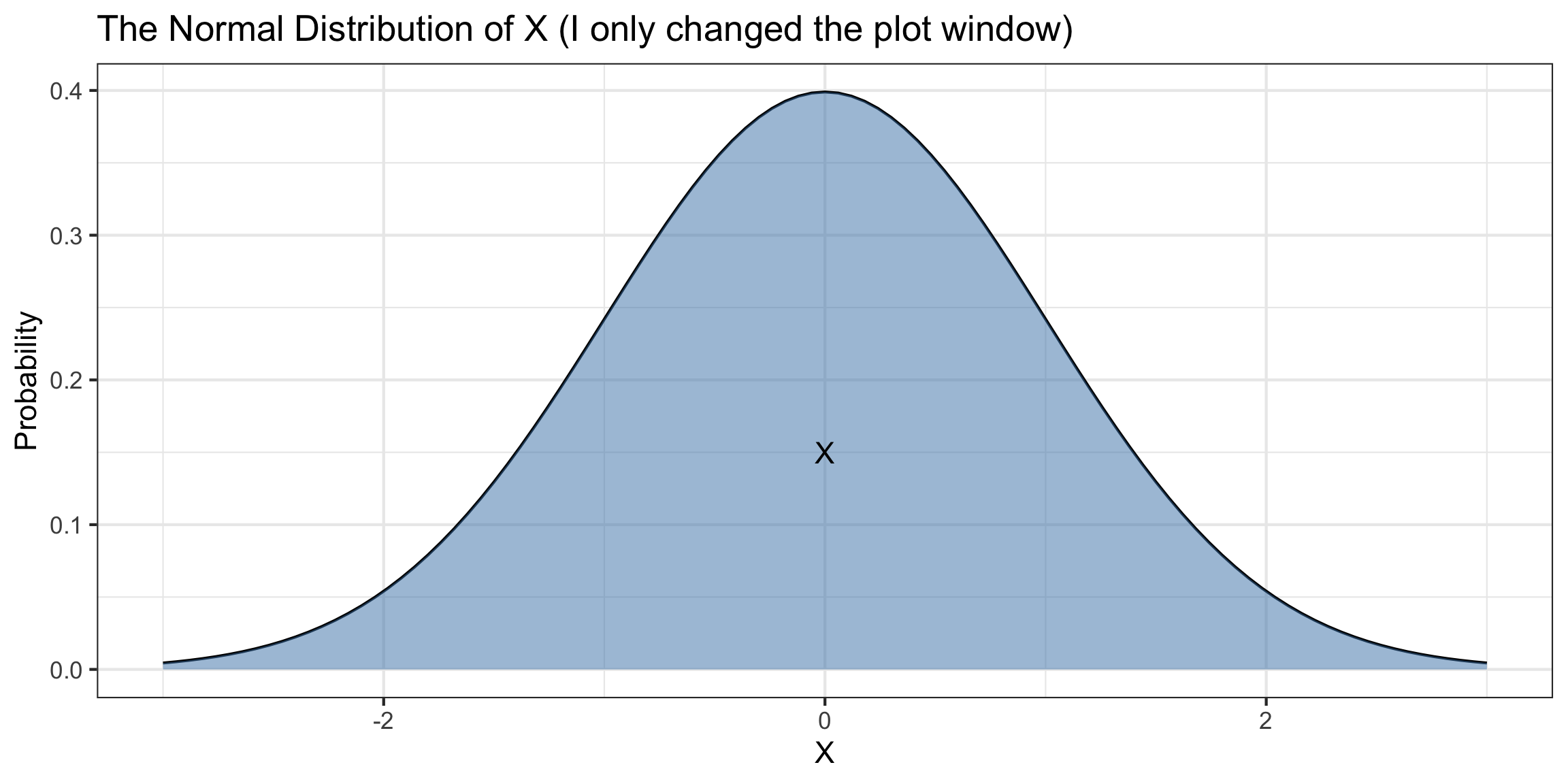

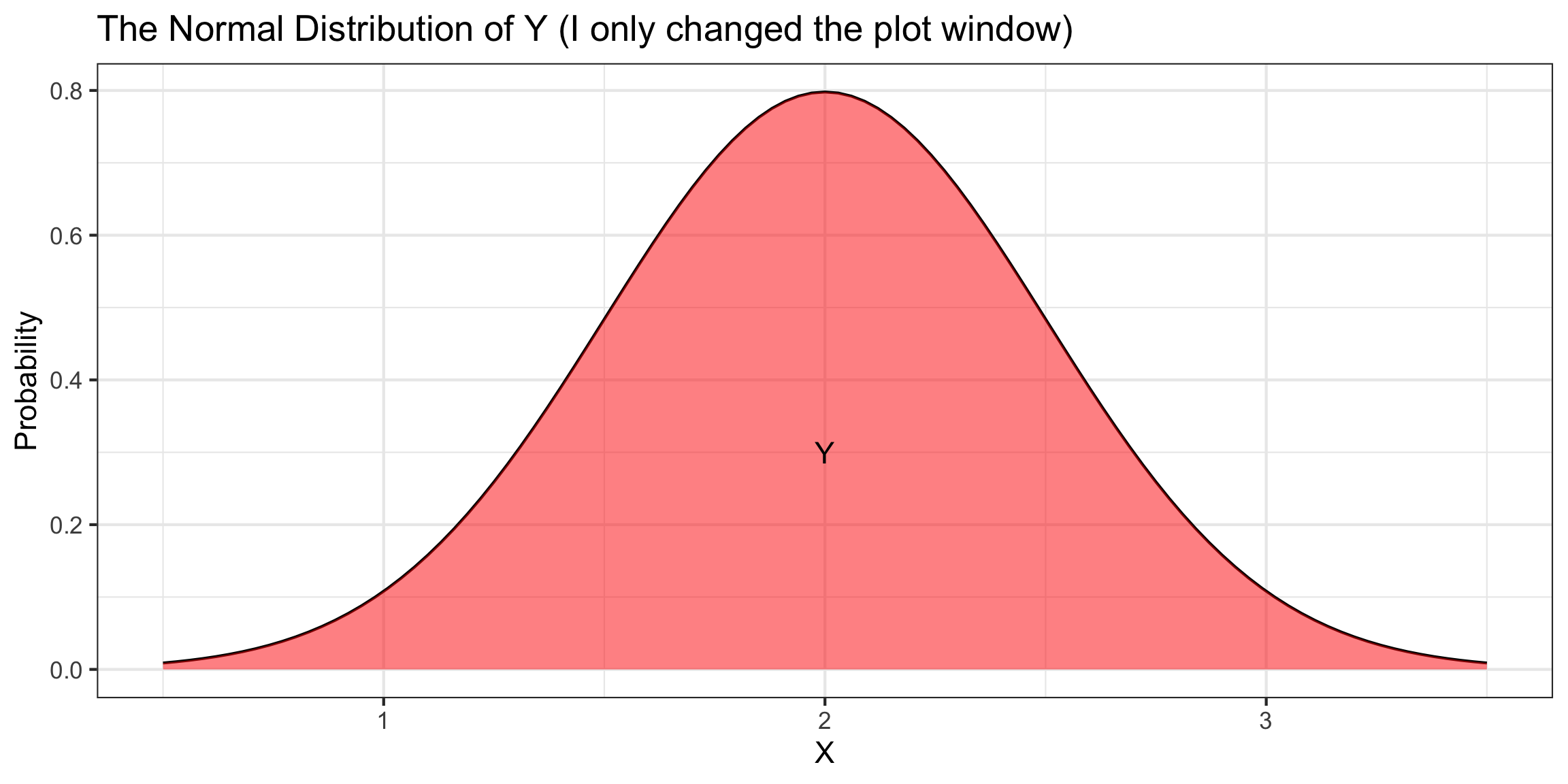

Suppose \(X\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\) and \(Y\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=2,\sigma=0.25)\).

\(X\) and \(Y\) have different means, heights, and widths…

- But the same shapes!

Scale and Translation Invariance

Suppose \(X\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\) and \(Y\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=2,\sigma=0.25)\).

\(X\) and \(Y\) have different means, heights, and widths…

- But the same shapes!

Scale and Translation Invariance

Suppose \(X\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\) and \(Y\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=2,\sigma=0.25)\).

\(X\) and \(Y\) have different means, heights, and widths…

- But the same shapes!

Standardization

Theorem: Standardization

Suppose \(X\sim\text{Normal}(\mu,\sigma)\). Then, \(Z = \frac{X - \mu}{\sigma}\) is a Normal random variable with mean 0 and standard deviation 1.

Standard Normal: a Normal random variable with mean \(0\) and standard deviation \(1\).

- We call the process of subtracting off \(\mu\) and dividing by \(\sigma\), standardizing.

- Useful Fact: If \(X\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=100,\sigma=10)\) and \(Z\sim\text{Normal}(\mu=0,\sigma=1)\), then,

\[P\Big[X < 90\Big] = P\Big[X<\text{ 1 SD below }\mu\Big] = P\Big[Z<-1\Big]\]

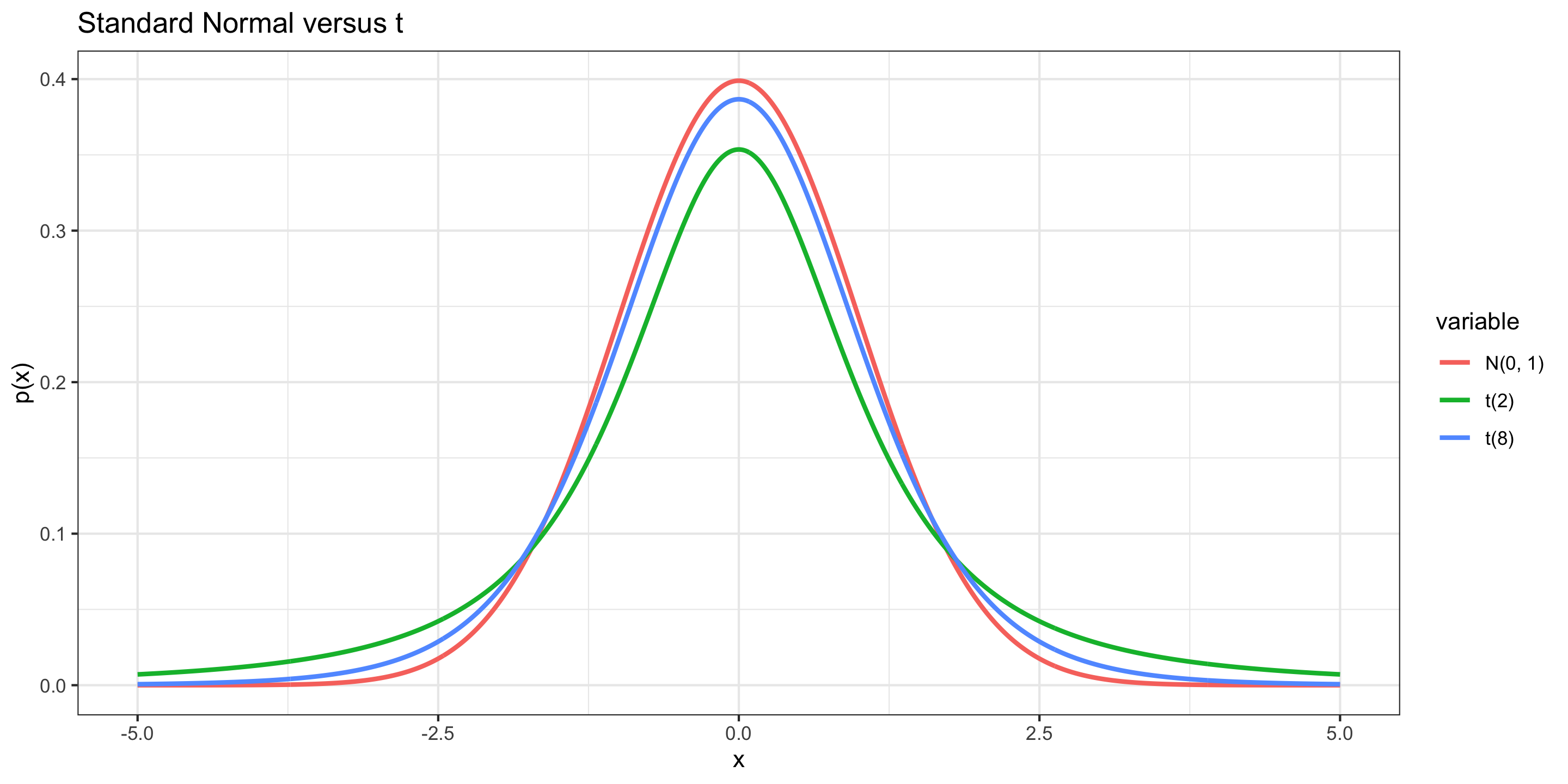

t distribution

t distribution

\(X \sim\) t(df)

Distribution:

\[ f(x) = \frac{\Gamma(\mbox{df} + 1)}{\sqrt{\mbox{df}\pi} \Gamma(2^{-1}\mbox{df})}\left(1 + \frac{x^2}{\mbox{df}} \right)^{-\frac{df + 1}{2}} \]

where \(-\infty < x < \infty\)

Mean: 0

Standard deviation: \(\sqrt{\mbox{df}/(\mbox{df} - 2)}\)

It is time to recast some of the sample statistics we have been exploring as random variables!

Sample Statistics as Random Variables

Here are some of the sample statistics we’ve seen lately:

\(\hat{p}\) = sample proportion of correct receiver guesses out of 329 trials

\(\bar{x}_I - \bar{x}_N\) = difference in sample mean tuition between Ivies and non-Ivies

\(\hat{p}_D - \hat{p}_Y\) = difference in sample improvement proportions between those who swam with dolphins and those who did not

Why are these all random variables?

- But they aren’t Bernoulli random variables, nor Binomial random variables, nor Normal random variables, nor t random variables.

“All models are wrong but some are useful.” – George Box

Approximating These Distributions

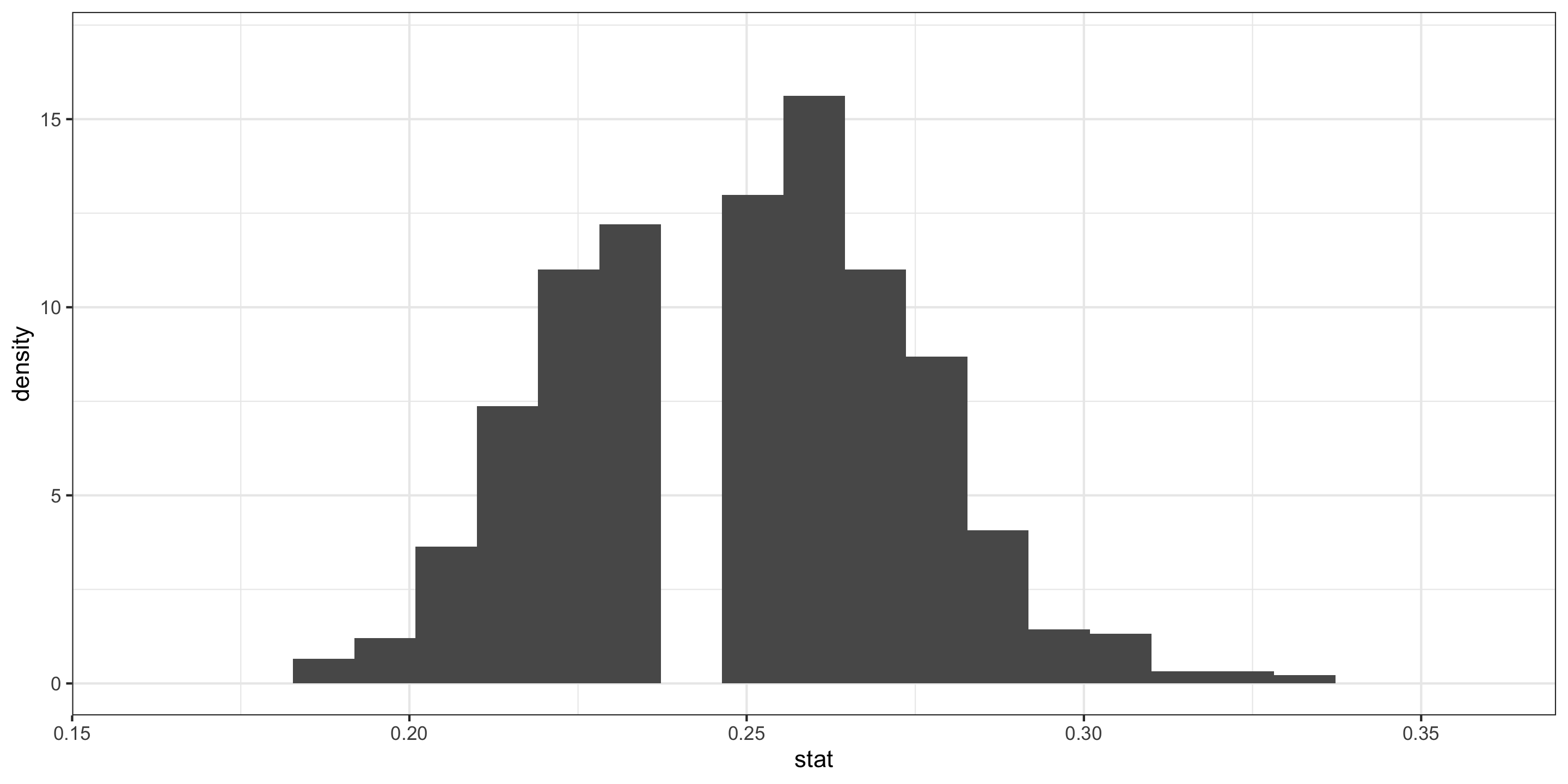

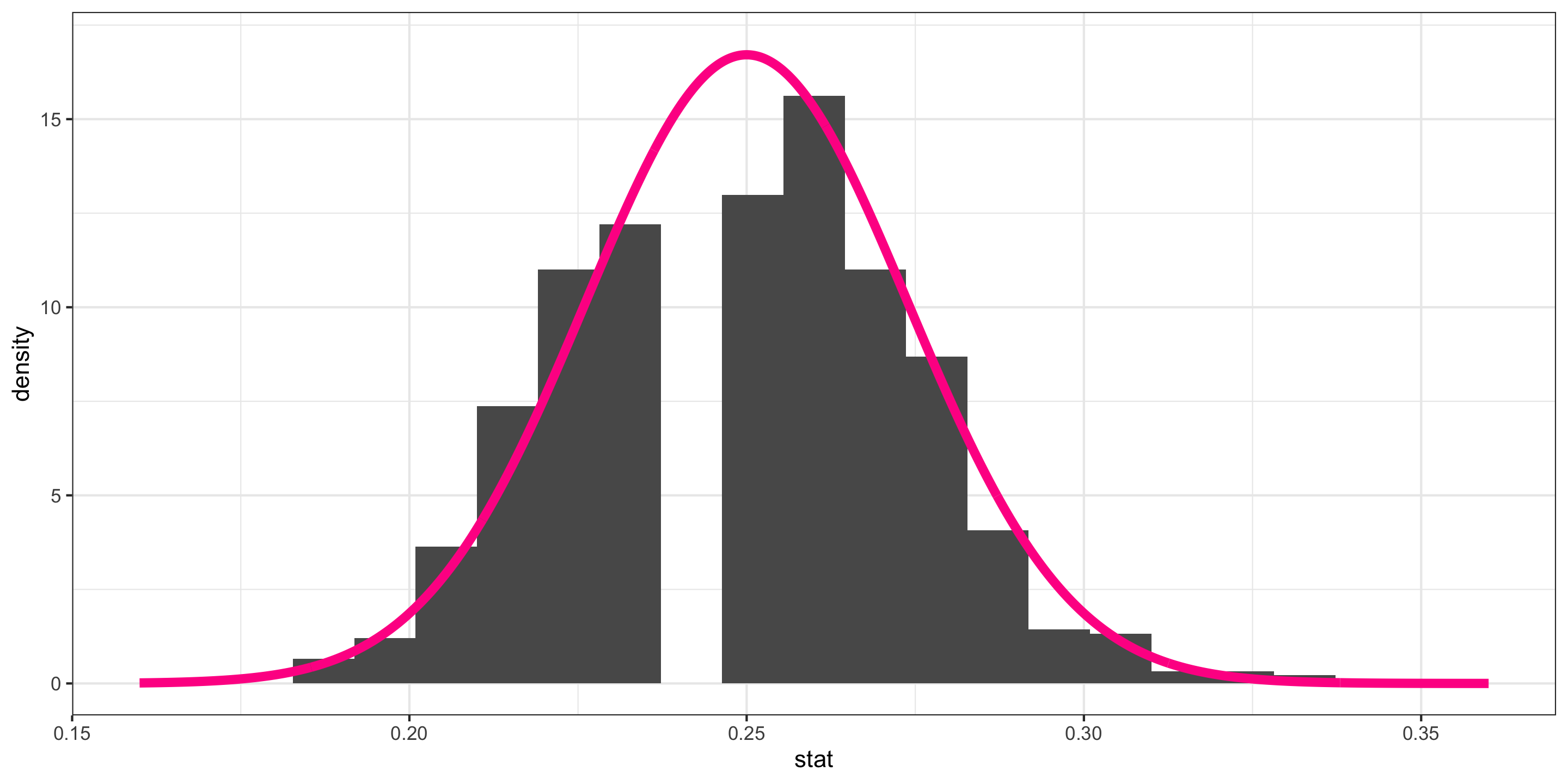

- \(\hat{p}\) = sample proportion of correct receiver guesses out of 329 ESP trials

We generated its Null Distribution:

Which is well approximated by the distribution of a N(0.25, 0.024).

Approximating These Distributions

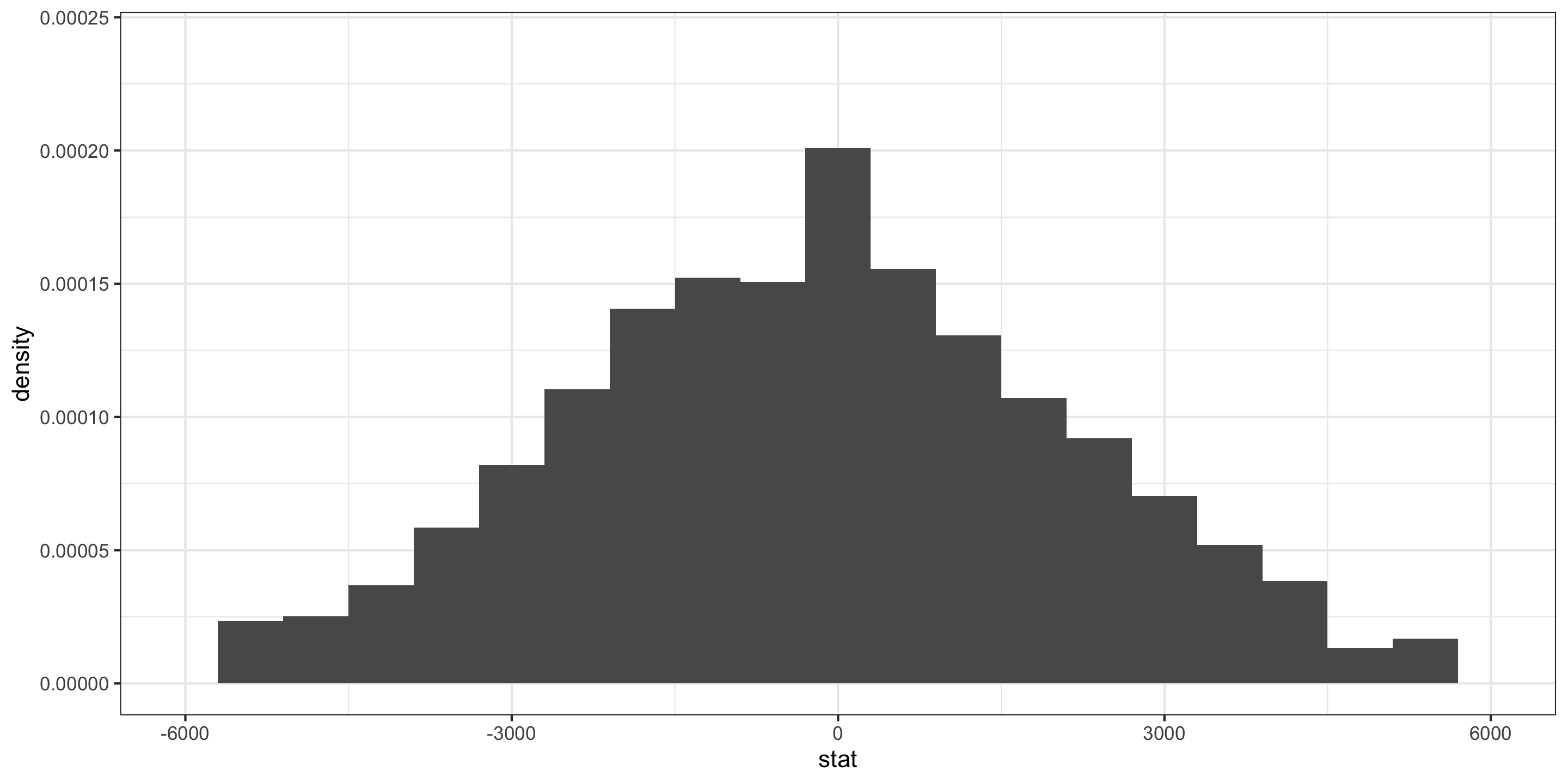

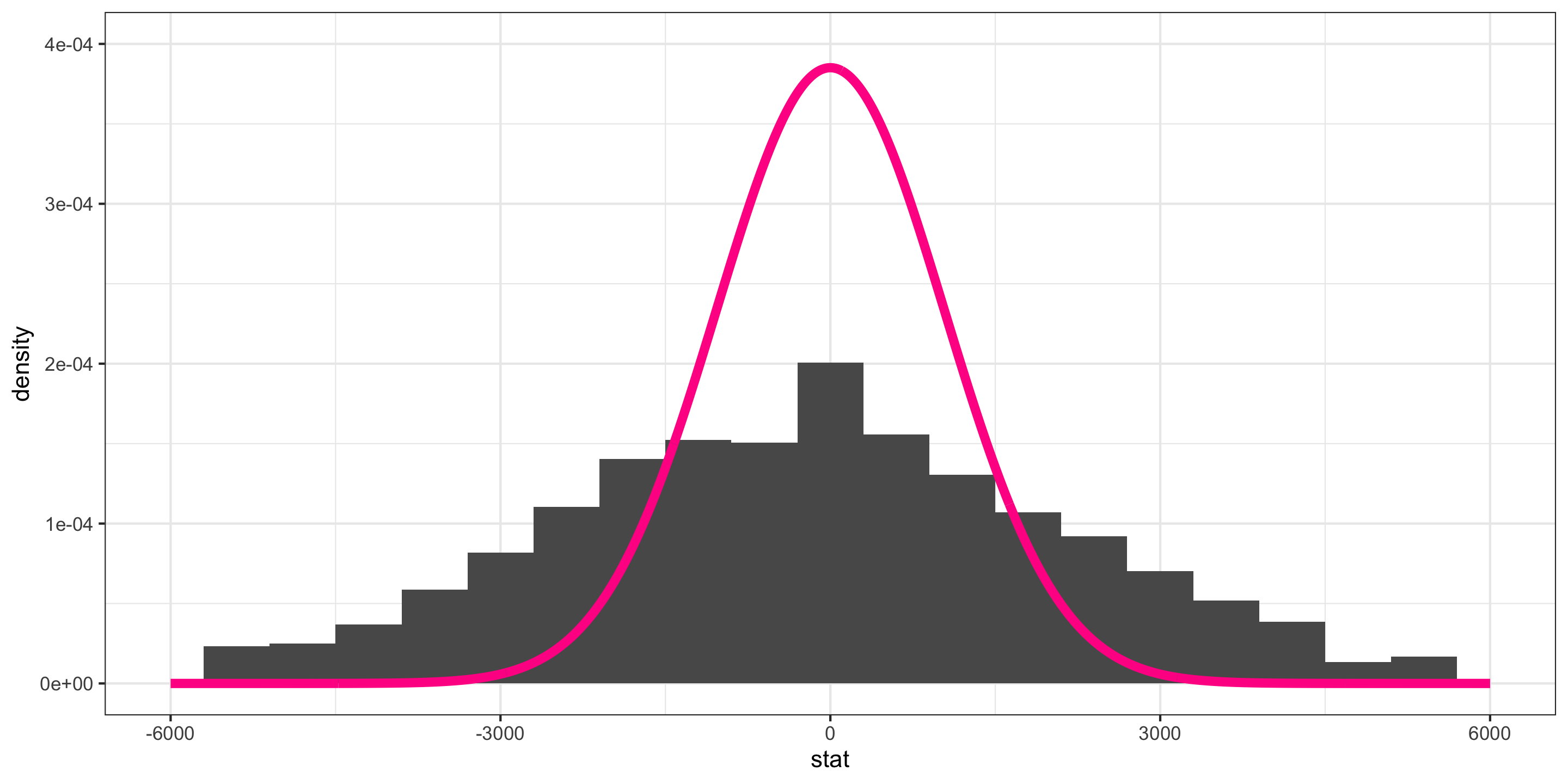

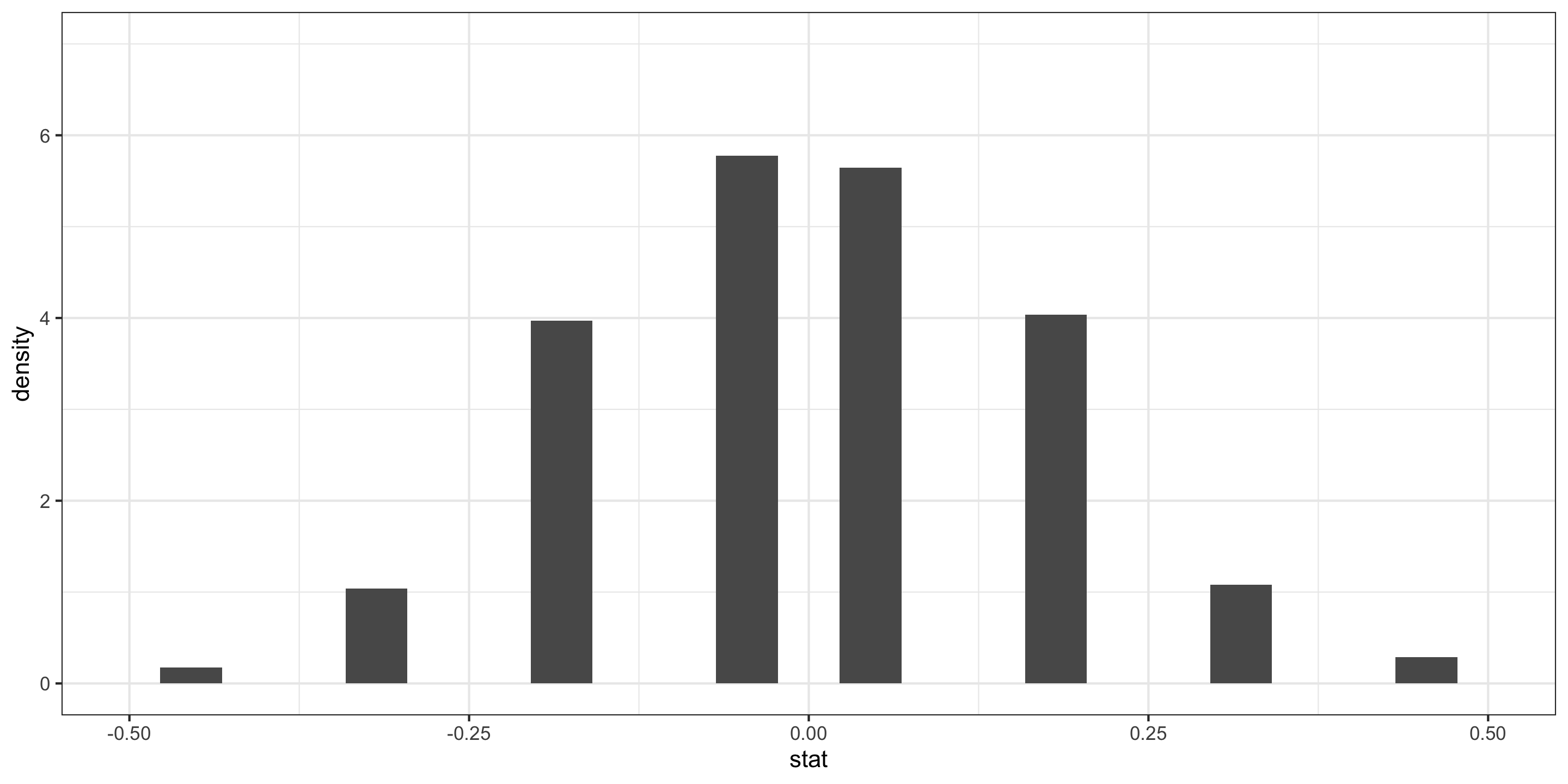

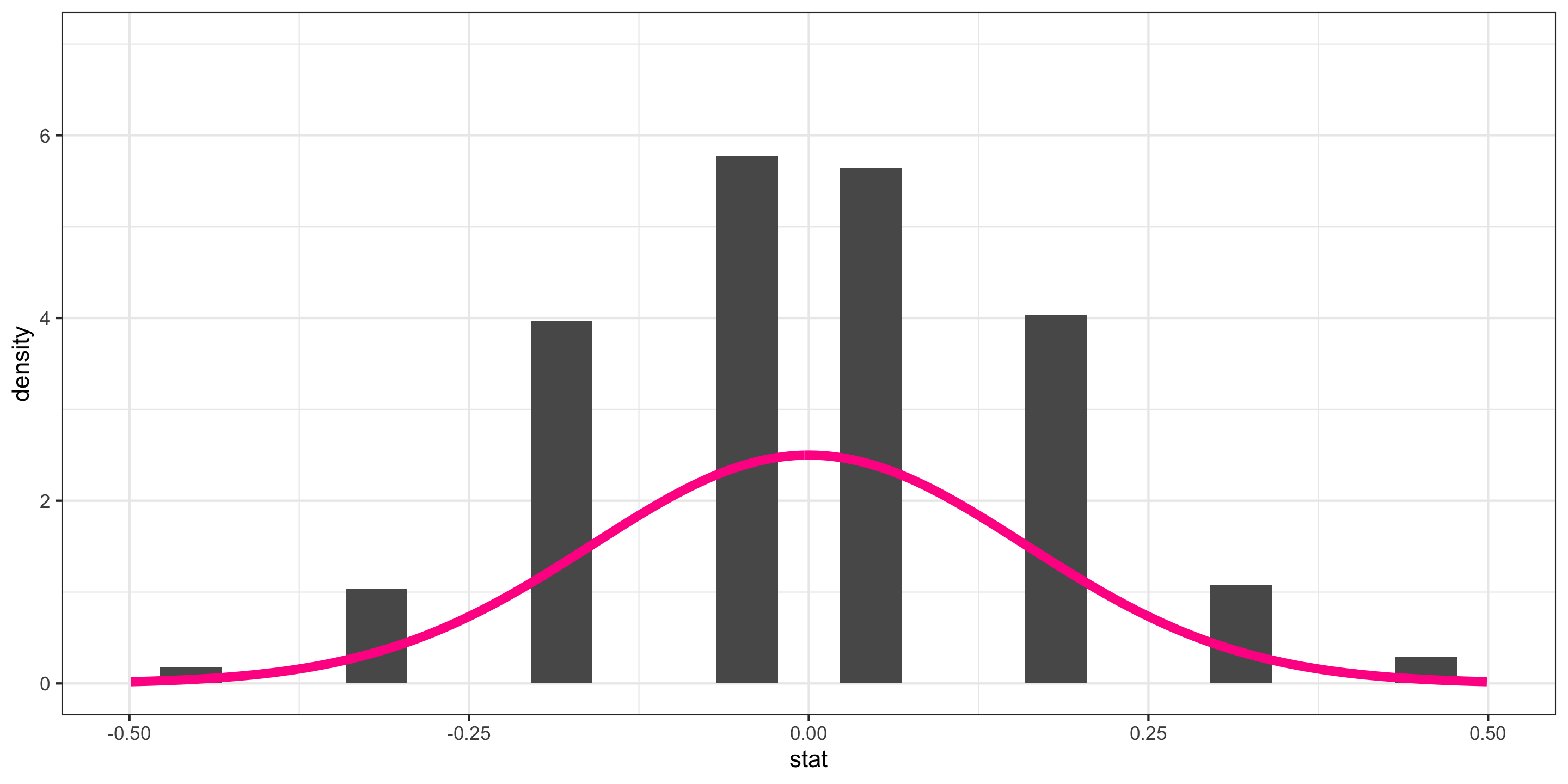

- \(\bar{x}_I - \bar{x}_N\) = difference in sample mean tuition between Ivies and non-Ivies

We generated its Null Distribution:

Which is somewhat approximated by the distribution of a N(0, 1036).

We will learn that a standardized version of the difference in sample means is better approximated by the distribution of a t(df = 7).

Approximating These Distributions

- \(\hat{p}_D - \hat{p}_Y\) = difference in sample improvement proportions between those who swam with dolphins and those who did not

We generated its Null Distribution:

Which is kinda somewhat approximated by the probability function of a N(0, 0.16).

Approximating These Distributions

How do I know which probability function is a good approximation for my sample statistic’s distribution?

Once I have figured out a probability function that approximates the distribution of my sample statistic, how do I use it to do statistical inference?

The Central Limit Theorem

Approximating Sampling Distributions

Central Limit Theorem (CLT): For random samples and a large sample size \((n)\), the sampling distribution of many sample statistics is approximately normal.

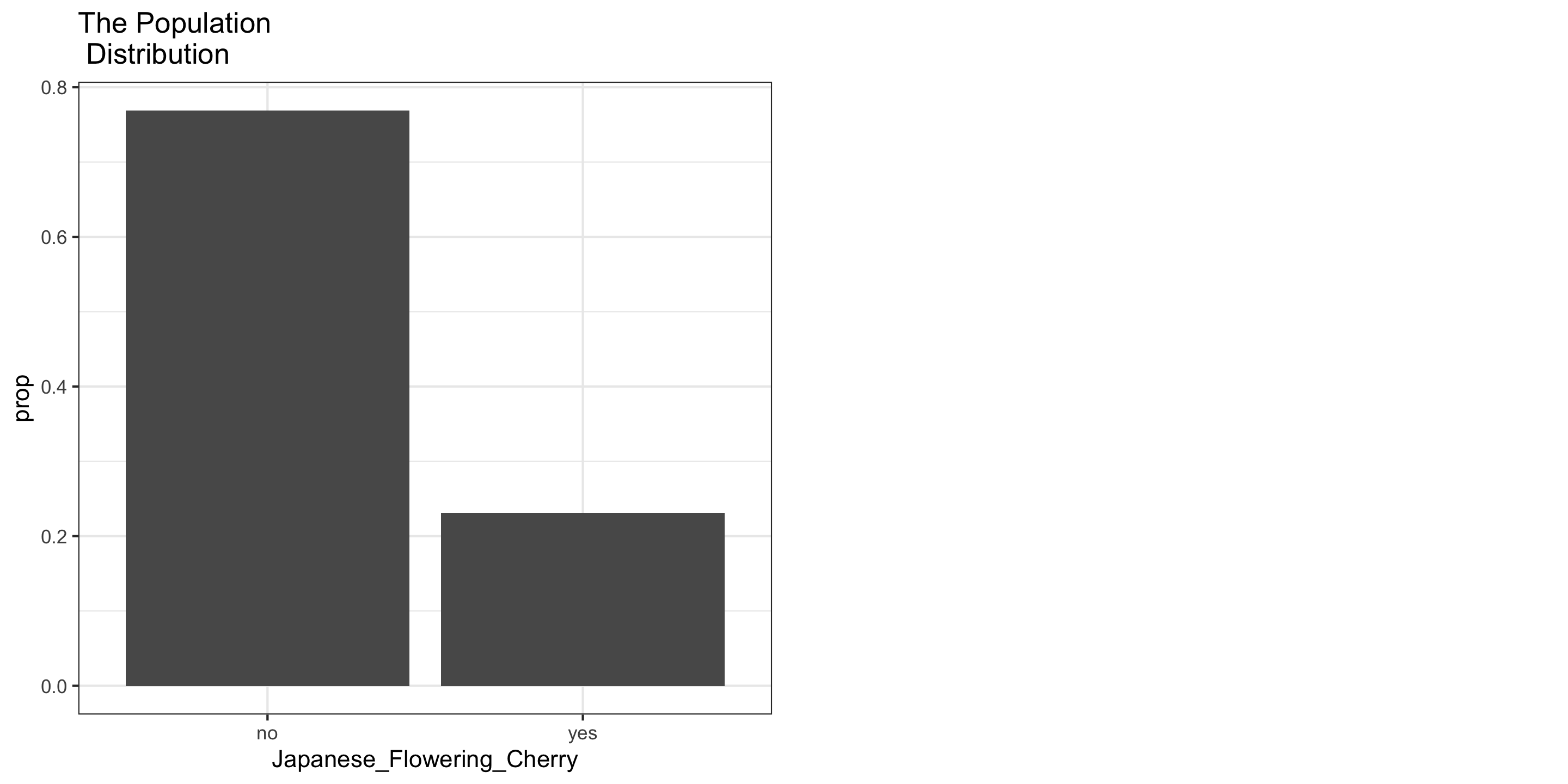

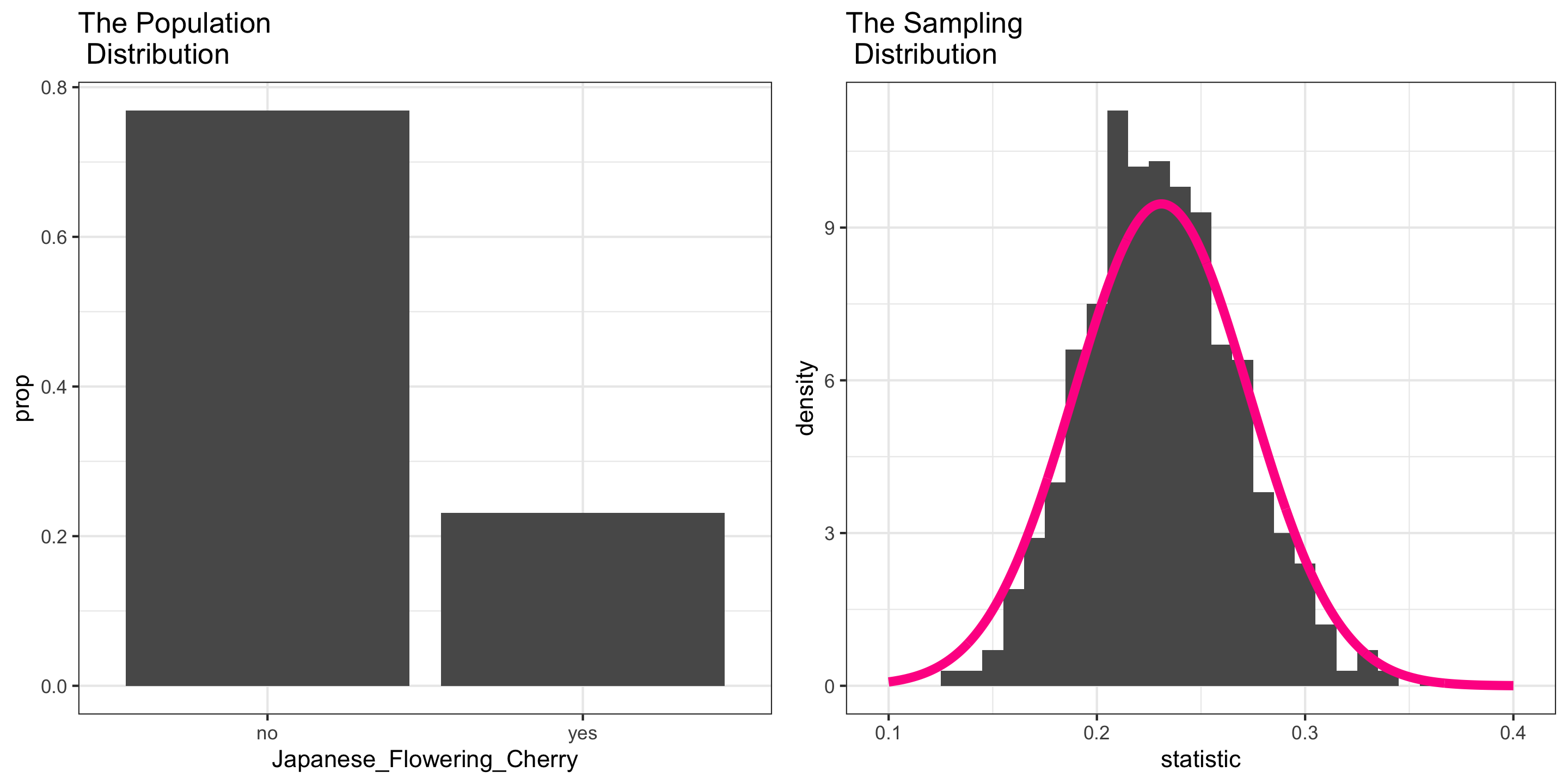

Example: Japanese Flowering Cherry Trees at Portland’s Waterfront Park

Approximating Sampling Distributions

Central Limit Theorem (CLT): For random samples and a large sample size \((n)\), the sampling distribution of many sample statistics is approximately normal.

Example: Japanese Flowering Cherry Trees at Portland’s Waterfront Park

- But which Normal? (What is the value of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\)?)

Approximating Sampling Distributions

Question: But which normal? (What is the value of \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\)?)

The sampling distribution of a statistic is always centered around: _____

The CLT also provides formula estimates of the standard error.

- The formula varies based on the statistic.

Approximating the Sampling Distribution of a Sample Proportion

CLT says: For large \(n\) (At least 10 successes and 10 failures),

\[ \hat{p} \sim N \left(p, \sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}} \right) \]

Example: Japanese Flowering Cherry Trees at Portland’s Waterfront Park

Parameter: \(p\) = proportion of Japanese Flowering Cherry Trees at Portland’s Waterfront Park = 0.231

Statistic: \(\hat{p}\) = proportion of Japanese Flowering Cherries in a sample of 100 trees

\[ \hat{p} \sim N \left(0.231, \sqrt{\frac{0.231(1-0.231)}{100}} \right) \]

NOTE: Can plug in the true parameter here because we had data on the whole population.

Approximating the Sampling Distribution of a Sample Proportion

Question: What do we do when we don’t have access to the whole population?

Have:

\[ \hat{p} \sim N \left(p, \sqrt{\frac{p(1-p)}{n}} \right) \]

Answer: We will have to estimate the SE.

Approximating the Sampling Distribution of a Sample Mean

There is a version of the CLT for many of our sample statistics.

For the sample mean, the CLT says:

Theorem: Central Limit Theorem

For large \(n\) (At least 30 observations),

\[ \bar{x} \sim N \left(\mu, \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \right) \]